In an attempt to describe the essential features of the novel, the Russian literary critic Mikhail Bakhtin (1895-1975) selected the enigmatic term “heteroglossia.” The concept of heteroglossia encompasses the novel’s unique tendency to be a “heteroglot, multi-voiced, multi-styled, and often multi-languaged” literary form, as compared to poetry, drama, or the epic.[1] For Bakhtin, the novel stands apart, a distinctive member of the realm of Literature, precisely because it combines such a diverse conglomeration of voices – those of social classes, ethnic groups, generations, political ideologies, etc.[2]

Libraries, too, embody the notion of heteroglossia, but on a larger scale. A typical library is a place where diverse works of literature – diverse voices – can be found all in one location. Compendiums of everything from Shakespeare’s plays to state histories, libraries strive to preserve, compile, and protect the multitude of different authorial voices that have contributed to the delightfully disharmonious din of both Literature and History.

However, as most librarians and archivists come to realize during their careers, it is impossible for a library to collect and preserve everything. Special Collections and rare book libraries in particular face this problem constantly – an indiscriminate approach to collecting would result in overflowing shelves belonging in the home of a bookish hoarder rather than a library.

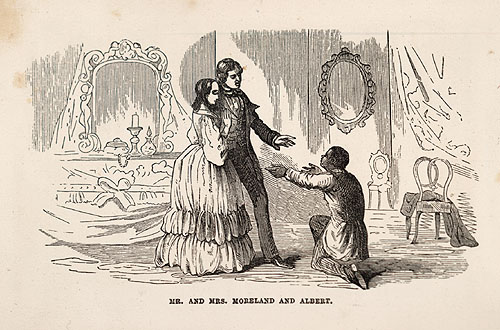

There is no precise answer to this question, but by and large the continued relevance (or irrelevance) of a work seems to be the most universally applicable solution. Some books in the collection, like Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn, are unassailable – they are in no danger of becoming pariahs. Others, like The Planter’s Northern Bride by Caroline Lee Hentz, have been deemed insignificant or as belonging to the losing side of history, which puts them in grave danger of being deleted from library inventories.

In a world as “contradictory and multi-languaged” as our own, libraries must be selective about the languages and voices they choose to collect, yet representative of a variety of distinctive dialects and socio-political and historical viewpoints. [3] Toeing the line between discriminatory selectiveness and an all-inclusive amassing of materials is perhaps one of the more vexing challenges that libraries face, but also one of the most thought-provoking.

If history had gone differently – say, if the Confederacy had won the Civil War – would the vehemently anti-abolitionist The Planter’s Northern Bride be the untouchable classic, and Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin the muted exile?

[1] Mikhail M. Bakhtin, “Discourse in the Novel,” in The Norton Anthology of Theory & Criticism, ed. Vincent B. Leitch (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2010), 1080.

[2] Ibid., 1078.

[3] Ibid., 1087.