News

Scholarly Perspectives on COVID-19, Part 9: The Solace of Art

January 26, 2021

January 26, 2021

Open gallery

This is the ninth story in a series on Southwestern faculty perspectives on severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) and coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Part 1 focused on biology, part 2 on mathematics, part 3 on economics, part 4 on sociology, part 5 on political science, part 6 on psychology, part 7 on history, and part 8 on religion.

As daily infection rates for COVID-19 continue to crest during this 12th month of the pandemic, many of us continue to stay at home, relying on streaming platforms, websites, and social media to engage with the art that helps us cope during times of anxiety and isolation. Making, sharing, and relating to one another through creative expression has been a boon to many as the pandemic continues to cause museums and small galleries to close and exhibitions to be postponed or even canceled. But as the economy struggles to recover from the recession, the impact on the arts remains particularly brutal: unemployment remains especially high among artists, and as many as 12,000 nonprofit arts and cultural organizations report that they are “not confident” they will survive the pandemic because although some museums and individual artists have been able to share their collections or convert their work to an online presence, patrons are staying away from brick-and-mortar institutions, and philanthropic giving has decreased. In addition, with many studios shut down or limiting capacity for health and safety, many artists are finding it difficult to access the resources they need, such as materials and tools, kilns and furnaces, wheels, and filtration systems. And then, of course, there is the tremendous difficulty of making art in a time of stress and uncertainty.

So while the arts are helping us to survive the pandemic, the prognosis for many artists and arts organizations looks rather grim these days.

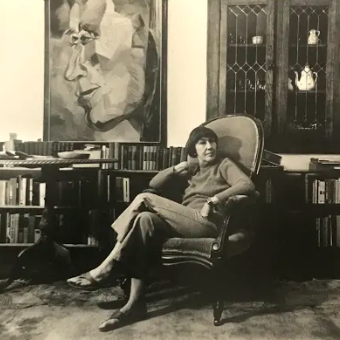

“You have some artists that I think just feel a bit lost and don’t have the inspiration or the drive or the headspace to make work,” says Ron Geibel, assistant professor

of art at Southwestern. “And for others, it has to do with access.” For example, artists who work in his primary medium, ceramics, may normally work with larger arts collectives but can no longer do so, so they have had to improvise makeshift studios in their homes. “But those are professional artists who understand how to work with those materials at home,” Geibel says; students may not have the training or the means to set up safe personal workspaces.

Still, many creatives who do have the means are responding directly to the pandemic, creating art out of loss: Beili Liu, an Austin-based artist, transformed surplus prayer flags from her 2013 public installation Thirst into masks. Street artists, graffiti artists, and muralists have expressed empathy, hope, and protest on walls and sidewalks across the globe. It’s an energy that often occurs in the weeks, months, and years following significant events, whether they are cultural traumas or historic victories to celebrate. “It usually takes people a second to start to process something like that before they start making work about it,” Geibel shares, “but there are artists who will make work in the current moment when it’s happening.”

Geibel himself is among the artists for whom making work “becomes your outlet—and it’s not that you’re removing what’s happening from your mind, but it’s just a way to continue your practice.” Deadlines for shows may have shifted, but those responsibilities remain; most artists cannot afford to simply stop making work for months on end, either financially or emotionally. “For a lot of us, especially for those in academia, we feel anxious when we’re not being productive. Even if it’s not completing a project, just by sitting down and sending out emails, there’s progress being made, so there’s some comfort in that,” he adds.

Last June, Geibel’s solo exhibition landscape was set to open at the gallery of the Austin Central Public Library. The show, which explores the cultural and political landscape of the queer history of Texas, was postponed to later this year, so despite some initial disappointment with the delay, Geibel is content to use the extra time to produce more works.

But besides the pragmatic impacts of COVID-19 on his work, Geibel’s research and thinking about specific pieces for the show have been revealing connections between the current public-health crisis and another recent pandemic: HIV/AIDS. One installation includes porcelain vessels based on both apothecary (i.e., pharmacy) jars from the Italian Renaissance and queries catalogued by those working at the Austin AIDS Hotline in the mid-1980s, which Geibel found during multiple visits to the archives of the Austin History Center. “You’ll have questions from people who think that they’ve been exposed or may have contracted HIV,” he describes, “and others are calling in with questions based on the lack of education: ‘Am I going to get AIDS from the collection basket at church?’ ‘What if I share a cigarette or if I’m sharing food?’ ‘Can I get it from a mosquito?’ ‘I’m taking my children to my brother’s, and he’s gay; are we going to come home with AIDS?’” Such questions may seem absurd now, Geibel says, but they reflect the uncertainty and ignorance of individuals and communities that inevitably result from lacking either access to up-to-date information about a novel disease specifically or scientific literacy more broadly. Similarly preposterous questions could be heard at especially the beginning of the COVID-19 outbreak: “Will I get the coronavirus if I order a product from China?” “Are 5G mobile phone towers causing or exacerbating the disease?” “Will ingesting bleach fight off the virus?” Unfortunately, just as they did during the early years of the AIDS pandemic, lack of information, misinformation, and disinformation have sown widespread confusion about COVID-19.

Another parallel the ceramicist draws between the AIDS and COVID-19 pandemics is the tendency to place blame for a disease on a particular group of people—a reaction indicative of prejudice or bias that often leads to discrimination. When pundits and even government leaders defied the World Health Organization’s recommendation to avoid the discriminatory naming of diseases by referring to the current pandemic as “the Wuhan virus,” “the Chinese virus,” or “kung flu,” Geibel was reminded of periodicals in the early 1980s that referred to AIDS not as “acquired immunodeficiency syndrome” but rather as “the gay plague,” “gay cancer,” or “gay-related immunodeficiency (GRID).” A New York Times article from May 11, 1982, for instance, is headlined, “New Homosexual Disorder Worries Health Officials.” Such misnomers erroneously attributed the cause of the disease while stoking fear of a misunderstood virus—fear that often manifested in intense homophobia. In a similar way, Asians and Asian Americans initially bore the brunt of racist verbal and even physical attacks because they were blamed for spreading COVID-19. “It was the exact same thing: taking this thing that is going to affect anyone and putting it on a group of people. It’s like we’ve learned nothing,” Geibel observes.

So as they did during the AIDS pandemic, many artists and arts organizations responded. They documented assaults on people of Asian descent as well as boycotts and vandalism of Asian-owned businesses, thereby raising awareness of xenophobia and racism. Fashion designers and stylists used their runway shows and social-media platforms to express condemnation of such abuse and discrimination. And writers, artists, and celebrities championed the positive contributions by artists of Asian heritage to combat pernicious stereotypes. “The act of making work on its own is political, and I think that artists are always fueled by scenarios like this,” Geibel explains. “Moments like this, it just fuels that fire to make work, to be creative.”

“Moments like this, it just fuels that fire to make work, to be creative.”

Given the undeniably significant roles that artists and art organizations play in expressing ideas, advocating for social justice, crossing cultural and political divides, documenting the human experience, and providing consolation and inspiration, it’s surprising and often frustrating that the need for and value of creative work—not to mention the funding of that work and of the institutions that support it—should ever be questioned. “In general, it’s always been ridiculous to have to justify the arts and why they’re important. And in moments like this, it’s more important than ever,” Geibel says. Unfortunately, “the second the economy starts to do poorly, it affects the art market.” So for the past year, many artists have been unable to sell their work for lack of buyers, artists who teach have seen their classes (and salaries) cut from low enrollment, and museums are suffering from lack of visitors, decreased or canceled grant funding, and reduced philanthropic giving, in part thanks to less-attended online fundraising events. The future looks even bleaker for small galleries, which, like local restaurants, are often barely treading water as it is and are consequently unlikely to survive the multiple months of closed doors necessitated by a pandemic. Geibel’s own dedicated students at Southwestern have been able to overcome the challenges of learning the technical aspects of hands-on processes during the pandemic, but the fate of art schools and especially of small arts centers and teaching collectives hangs in the balance; even at the historic San Francisco Art Institute, only a last-minute influx of donations in July 2020 barely kept the doors of the 149-year-old college open.

Neverthless, Geibel remains hopeful. “As a whole, artists in general always come out of these scenarios a little stronger,” he says. Indeed, creatives have had to get creative with how they create, designing digital spaces and hosting virtual events for their work, organizing community fundraisers, soliciting commissions and offering gift cards for future projects, converting workshops to online courses, and sharing resources among their fellow artists to pay the bills and keep the lights on. And Geibel’s observation certainly holds water if we consider the triumphs of art during previous dire straits, whether it was the AIDS or 1918 flu pandemics, economic depressions or recessions, and world wars or revolutions. The COVID-19 crisis, too, will have its end. In the meantime, we should appreciate that we can take solace in the work of artists as one positive legacy of these strange and stressful times.