News

Art History Mystery, Part 1

July 02, 2019

July 02, 2019

Open gallery

In late July 1941, spirited young artist Elizabeth Tracy Montminy (1911–1992) began painting a mural in the post office of Kennebunkport, Maine. Fascinated by murals since the age of 12, Montminy was a graduate of Radcliffe College—Harvard University’s all-women counterpart—in Massachusetts and the Art Students League in New York City. Her work had recently earned her the prestigious Guggenheim Foundation Fellowship. Between 1934 and 1941, she was commissioned five times by the U.S. Treasury Department’s Section of Painting and Sculpture (renamed the Section of Fine Arts in 1939 and often abbreviated as “the Section”) of the Work Projects Administration (WPA), a New Deal agency whose purpose was to provide paid work for 5,000 unemployed artists during and after the Great Depression. The hoped-for effect of the WPA murals, which would adorn post offices and other government buildings around the country, was to boost Americans’ morale through the representation of uplifting themes, such as historical victories, courageous acts, or local color. Montminy’s subject for Bathers would be “a group of summer resorters relax[ing] on the sand at Goose Rock Beach.” She would be paid $700 in November of the same year for completing her playful work.

Not four years later, on April 2, 1945, Life magazine would announce that the mural had been unceremoniously pulled down. It was replaced by a historical painting by maritime artist Gordon Grant (1875–1962), who, bowing to the conservative locals’ preferences, depicted the harbor of Kennebunkport in its heyday as a shipbuilding and fishing village in 1825.

The dismantling of Montminy’s mural had followed years of scathing critique, often delivered within earshot of the artist herself as she painted on site in the post office. Although the local postmaster, Wilbur F. Goodwin, and the Section had authorized and continued to defend Bathers and the painting had plenty of supporters in the local community, the mural, with its swimsuit-clad vacationers and colorful umbrellas, had been variously labeled “repulsive” and “offensive.” The main cause of vitriol seemed to be the “disgusting, corpulent bathing figures,” which were mercilessly condemned for being “utterly grotesque and cheerless,” “fat hussies,” and “shameless maids.” Most famously, the painting drew fire from Booth Tarkington (1869–1946), a two-time winner of the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction who is now mostly forgotten but was once considered the greatest living author of the 1910s and 1920s; he skewered the mural as an “inartistic” and “dismal” “combination of Coney Island and Mexican realism.” (Of course, one might reasonably question his opinions as an art critic considering that Tarkington’s eyesight had begun to fail in the 1920s, and by the early 1940s, he was blind.) His friend and coauthor Kenneth Roberts (1885–1957) took up the charge as well. A Kennebunk-born journalist turned bestselling author who specialized in regional historical fiction (and was noted in a 1940 issue of Time magazine for his famous rages, his xenophobia, and his disgust at interracial “mongrelization”), Roberts complained that “the painting … is an eyesore and the whole town is ashamed of it.”

The mural’s detractors were so vocal that U.S. Senate Minority Leader Wallace H. White Jr. (1877–1952), of Maine, entered the fray. His primary grievance was that “[t]he mural is a picture, which, to speak frankly, depicts a number of fat women, scantily clad, disporting themselves on a beach.” Indulging in what we now refer to as body shaming, the senator argued that “it was the bulges, fore and aft, they objected to.” Senator Ralph Owen Brewster (1888–1961) echoed White’s criticism: “Our only objection was that the murals depicted feminine forms absolutely foreign to the great state of Maine. Our Maine women do not bulge fore and aft in this unsightly manner. Our womenfolks bulge in only the most delightful ways.”

Back in Kennebunkport, the critics continued to spread their snide censure of the painting, even hinting ominously that Montminy’s beachgoers were modeled on Russian peasants and that the artist herself might harbor Communist sympathies—an insidious rumor in the years leading up to the First Red Scare of 1947 and the McCarthyism of the 1950s. When the Federal Works Agency refused to pay to replace the offending mural, the Kennebunkport locals themselves raised more than $1,000 to install Grant’s painting glorifying the town’s shipbuilding past. Because removing a work of art from a federal building requires the politicking of friends in high places, Senator White attached a special rider to a $3 billion appropriations bill that ultimately authorized the removal of Montminy’s Bathers from the Kennebunkport P.O. Signed by President Harry S. Truman, the act of Congress would spell the end of Montminy’s controversial work in the spring of 1945.

When Montminy got the news, she was living in Austin, Texas, with her husband, fellow artist Edmond Pierre Montminy, who was working at the University of Texas. Having successfully and without kerfuffle completed four other murals for the WPA, which can still be found today in Massachusetts, Illinois, and elsewhere in Maine, Montminy was crushed by the government’s decision, arguing that Bathers merely exhibited “a Renaissance influence in which the arabesque dominates” and referring to criticisms as “the squealing of some cachectic dowagers.” She contacted the leaders of the Section to discover the fate of her fifth WPA mural but to no avail. Was it painted over? Was it being stashed away somewhere in unwelcoming Kennebunkport? Had it been transported back to the Section in Washington, DC, to be archived among other federally commissioned artworks?

No one knew. The mural had vanished. Montminy never saw her work again.

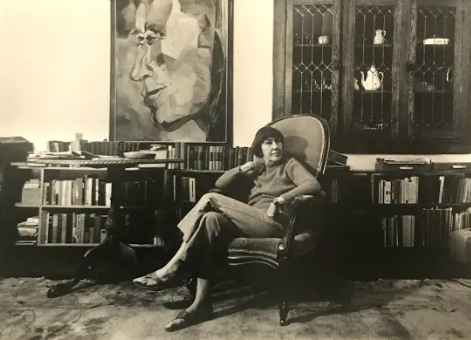

Almost 75 years after the disappearance of Bathers, in the summer of 2019, Southwestern Professor and Chair of Studio Art Victoria Star Varner and three of her students, Sophia Anthony ’19, Kati Hellmer ’19, and Danbi Heo ’19, are on the case. Varner studied under Montminy at the University of Missouri–Columbia (UMC), where Montminy had joined the faculty the same year as a professor of painting, drawing, and, eventually, mural painting. While working toward her M.A. in painting, Varner had the opportunity to contribute to a mural Montminy designed and painted with students at UMC. So the Southwestern artist and professor has a strong personal connection to the hunt for her mentor’s missing mural.

Oddly enough, Montminy had never mentioned to Varner that one of her murals had once been the center of a national controversy. The Southwestern professor only discovered the story of Bathers this year, when she was contacted by UMC, which is currently restoring another Montminy mural on their campus and wanted Varner’s input on having worked with her mentor. It was only then that Varner looked into Montminy’s history and encountered tales of the Kennebunkport fiasco. Learning that the scandalous mural had gone missing only motivated Varner to delve deeper.

“Many have tried to find the mural, and all have failed so far,” Varner says. “But we’re going to try to find it. There are still breadcrumbs.”

The research team will spend 10 days on a whirlwind investigation of archives at the Montminy Art Gallery at Boone County History and Culture Center, in Columbia, Missouri; the National Archives Research Center and the Archives of American Art at the Smithsonian Institution, both in Washington, DC; and the Kennebunkport Historical Society, in Maine.

Varner writes, “Bathers touched a nerve in Kennebunkport, and Montminy’s situation became a nexus of sociopolitical topics, including gender, body size, class, and political jockeying set within a culture of fear of the Communist threat and consequent suspicion about the artist’s political sympathies.” In searching for the artist’s lost mural, Varner says the group is “driven to avenge the unfettered sexism that Elizabeth Tracy Montminy endured and the national disgrace that followed.”

Stay tuned for the next installment of our “Art History Mystery” to find out what our intrepid researcher–detectives find during their trips to Missouri, DC, and Maine. Meanwhile, Varner encourages others to report any information they find about the missing mural to her at varnervs@southwestern.edu. This project is funded by a competitive faculty-development grant and friends of Sarofim School of Fine Arts.

Further reading

Marling, Karal Ann, Wall-to-Wall America: Post Office Murals in the Great Depression (University of Minnesota Press, 1982), pp. 272–282

New England Historical Society, “The Missing Kennebunkport Mural of the WPA”