News

Making a Difference

From Senegal to New York City, Kadidiatou Magassa ’13 has served communities as a Peace Corps volunteer, a domestic-violence case manager, and a coordinator for a children’s nonprofit.

November 27, 2019

November 27, 2019

Pushing beyond your limits

One might think that engaging in community service during trips to visit family in Africa while in high school might constitute enough of a challenge, but when Magassa was choosing where to attend college, she decided to do what few East Coast students would do: she traded the familiarity of life in the most populous city in the U.S. for a liberal-arts education at a small university in the small town of Georgetown, Texas. “I am someone who really likes to push myself out of my comfort zone,” she declares with a laugh.

Reflecting her lifelong desire to help those who need it most, Magassa dedicated her studies at Southwestern to “understanding what governments do to assist their populations—and what they don’t do—and figuring out development solutions to better assist the populations that are underserved.” She decided to major in international studies with a disciplinary focus in political science and a geographical emphasis on Africa. While at the University, Magassa was mentored by what she calls the “amazing” professors of the Political Science Department, including Shannon Mariotti, Bob Snyder, and Alisa Gaunder. They “were just really helpful in providing me with new perspectives in how to look at things academically,” she recalls. Mariotti, for instance, pushed her to new and unexpected limits of thinking about things in different ways. “Dr. Bob,” as she refers to him affectionately, kept her motivated and never allowed her to give up, even when she really wanted to. And Gaunder, who was Magassa’s advisor, “really pushed me to think more of myself,” she says, “to expect more from myself, and to not just take the easy way out of things.”

Beyond the faculty, SU’s assistant dean for student multicultural affairs was another mentor who was instrumental in helping Magassa determine her academic and career paths. “Terri Johnson helped me understand what it means to give back and what it means to appreciate diversity,” she reflects, “really taking different perspectives in mind and taking the time to actually listen to what people want, which helps you provide them with a better life.”

Joining Southwestern’s Coalition for Diversity and Social Justice (CDSJ) also helped shape Magassa’s future. She says that the CDSJ, which is an umbrella organization for other multicultural student groups on campus, is “the best of all worlds” because she could broaden her perspective on different people, ethnicities, and backgrounds. Through the CDSJ, she had the opportunity to work with at-risk populations throughout Texas, which helped her learn how to be respectful of different environments, cultures, and thought processes.

Serving the underserved

“Being part of the CDSJ just gave me a great lens as to what to expect when I went to the Peace Corps,” says Magassa, “of just being in an environment that’s very different but understanding what it takes to appreciate that environment—to be willing to learn from a different environment and different people and different lifestyles, but also, more importantly, to be respectful and not just tolerant. The CDSJ was the organization that put me on the path to want to go to the Peace Corps even more.”

“Being part of the CDSJ just gave me a great lens as to what to expect when I went to the Peace Corps.”

That decision to become a Peace Corps volunteer initially came after talking briefly with a recruiter who was visiting the Southwestern campus one day. As with her move from NYC to Texas, Magassa says she was again feeling compelled “to push myself out of my comfort zone and try new experiences, knowing that I was going to be scared but also knowing that I would be fine.” Moving from the U.S. to another country for two or more years and not traveling home during that time to visit family or friends was just the challenge she was looking for. She had studied abroad twice while at Southwestern—once in Lesotho, a country about the size of Belgium that’s completely surrounded by South Africa, and once in her parents’ home country of Mali—but she wanted to see how she’d weather living more than six months in a developing country without the safety net of staying at her grandmother’s home or living with a host family. “The Peace Corps was a great opportunity to go somewhere and dedicate two years of your life to help a community,” she reflects. “You don’t know what you’re going to get out of it, but that was my entire goal when I started my academic career: to serve underdeveloped populations.”

With the support of her fellow CDSJ members and her faculty and staff mentors, Magassa submitted her application to join the Peace Corps during her senior year. While she waited for the decision, she graduated from SU and joined the Office of Admission as a full-time recruitment coordinator. She remembers feeling nothing but love and support from her supervisor, Christine Bowman ’93, who is now dean of admission and enrollment services. “She was amazing when I first told her I was leaving,” Magassa recalls. “I think that comes from also being an alum, but she was so supportive and really loving [during] my transition. That’s something I can say for everyone: my three professors, Terri, Christine—they all supported me during my service.”

The power of perseverance

Magassa was stationed in Dioulafondou, a little-known village in the region of Kedougou in southern Senegal. When she visited her site, she compared the village with her alma mater. “I’m excited about the small community, though; it reminds me a bit of Southwestern,” she wrote in her blog in 2014. “SU is a very close-knit community where you may not know everyone, but there is a true sense of support and understanding of the importance of being a safety net in case one needs to break their fall. [Dioulafondou] is small enough where I feel like I will have the support I need to resemble the feeling of a close-knit family.”

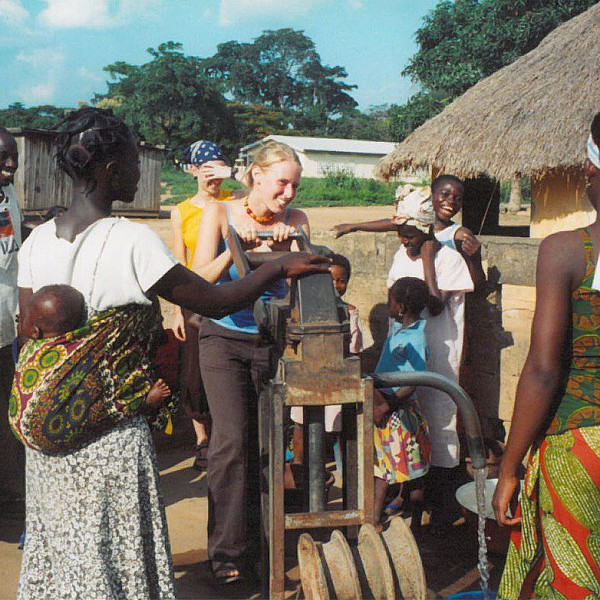

Magassa would rely on her SU, local community, and Peace Corps networks of support during her experience, which volunteers know to expect but can never fully prepare for: living in a remote locale with no electricity and no running water. In 2014, Dioulafondou comprised approximately 29 residential compounds and 360 people. When describing the terrain, Magassa laughs when she characterizes the local transportation as “terrible” because transit actually meant having to walk for kilometers through forest on small unkempt trails and roads. She also remembers hand washing her laundry, which entailed collecting water at a pump—and consequently being stung repeatedly by bees.

Like almost any Peace Corps volunteer, the SU alum felt discouraged during her first several weeks in Senegal. She worried that she wouldn’t be able to withstand the heat. She lost 40 pounds in single month because her access to nutritious food was severely limited. She was concerned about being able to communicate with her Francophone neighbors—although she does give a “shout-out to my French professors [at SU], Dr. Prevots and Dr. Mathieu, [because] they prepared me for the worst.” She had to set boundaries with her host family so that she could maintain some semblance of privacy. And she was frustrated by the lack of hygienic standards that inevitably led to illness among community members—Magassa herself suffered that “quintessential coming-out-of-both-ends illness that so many Peace Corps volunteers endure,” she shares.

However, the SU alum secured her footing by digging in. In the Peace Corps, she explains, “We have what we call ‘a six-week challenge,’ which is to stay in your village for six weeks without leaving. Typically, what happens after the second week [is] you think, ‘I can’t do this! I have to go where people speak English, where people eat American food.’” But Magassa completed her six-week challenge, staying put in Dioulafondou and learning the local dialect, which ultimately helped her gain her neighbors’ trust “that I was here for the long haul.” She says building the villagers’ confidence cemented “the bond that I needed to create with my community members [so] we [could] all get along and work as best as possible with one another.”

In addition to sheer perseverance, Magassa remembers that maintaining her sense of humor helped her cope. She met with a fellow volunteer who reminded her to appreciate the opportunity but to also recognize that she could leave Senegal at any time, which helped alleviate her anxieties. And her spirits were buoyed by her Southwestern family: her former faculty and staff mentors would send her care packages, “so I felt the love from SU even though I wasn’t there,” she says, “and I think that’s why my connection to SU is still really strong.”

The SU grad reflects that although life in the Peace Corps was quite an adjustment, she did feel mentally prepared at least in the sense that she went with no expectations. “A lot of people go with so many expectations of ‘this is what I’m going to accomplish’ and ‘this is what I’m going to do,’ and then they are sadly disappointed and leave early,” she observes. “I had the mind frame of ‘I’m up for anything. Anything can happen, especially for two years.’ Of course I created goals and accomplishments of what I wanted my service to look like, but really having the mind frame of ‘anything is up for grabs’ really helped me.”

Making a difference

The goals Magassa had set for herself included broader Peace Corps aspirations, such as promoting world peace and friendship, meeting the basic needs of those living in a developing region, and promoting a better understanding of the U.S. Her personal objectives included “mak[ing] a difference” and “learn[ing] to listen better.”

She would achieve those goals in part by helping to raise funds for a scholarship program that would help pay the fees for middle-school girls in her village. But her assigned role was preventative health educator, focusing on malaria prevention, maternal and child health, and water-sanitation and hygiene projects in Dioulafondou and multiple partner villages. “With those three different areas, I would help the village determine what assistance they needed or what projects they wanted to start or continue,” Magassa describes. “Then, I would basically be a facilitator, and it would be the community’s role to start the project and to sustain it.”

Harkening back to lessons learned from her Southwestern Experience, Magassa knew that listening to what her community members truly wanted and needed was crucial.

Those projects were many. Magassa taught school children about bacteria and the importance of handwashing. She trained healthcare providers living in the community how to detect and prevent malaria—and encouraged symptomatic community members to seek out those health workers. The SU alum loved creating educational materials: she helped produce a radio show about how to preempt the transmission of disease, and she and several other Peace Corps volunteers hosted a theater tournament in which they presented skits and information sessions about the importance of such measures as sleeping under nets to prevent infection by malaria-bearing mosquitoes. One of her favorite projects was planning soccer tournament for men who were only allowed to play if they participated in lessons on family planning and sexual and reproductive health.

“But one of my favorite things to do was to sit with the elderly women and pop peanuts,” Magassa fondly recalls. As a subsistence-farming community, Dioulafondou produced, harvested, and used what they grew, including cotton, corn, rice, and peanuts. “When the peanuts were ready, it was a task,” she recalls, because “we had acres and acres and acres of farms. So these aren’t small farms; they’re huge farms. We’d uproot the peanuts from the ground. We would then have to pop them to be able to cook with them.” Magassa preferred preparing the peanuts with the elderly women because the younger women tended to gossip; the elders were more likely to tell tales that helped the SU grad better understand African culture. “They were really wise and funny,” she shares. “They had great stories to tell, like really great fables and folktales.”

Giving back to the community

The two things Magassa values most about her Peace Corps experience were building relationships with her community members and being able to have a sustainable impact on her community—to create change that “lives beyond when you leave,” she says.

After her first two years of service, Magassa moved from Dioulafondou to Dakar, Senegal’s capital, to serve as a multimedia and communications coordinator, in which she would promote the work that other Peace Corps volunteers were engaged in throughout Senegal. She returned to the U.S. and her home state of New York in April 2017—she had spent three years abroad, much longer than her original test of living in a developing country for at least six months. Her first year back, she worked at a Bronx-based organization called Sauti Yetu Center for African Women and Families. There, Magassa continued to work toward serving underserved communities as a case manager for women from Africa who had survived domestic violence, including rape, abuse, and genital mutilation. She says she enjoyed using data to evaluate the organization’s current initiatives and to implement new programs to help immigrant women throughout the five boroughs.

Today, the SU alum works as a coordinator for the Harlem Children’s Zone, a nonprofit that provides family, social-service, health, and community-building programs to support poverty-stricken youth, enabling them to attend and graduate from college and become independent adults. There, too, Magassa enjoys assessing how effectively the nonprofit is serving its constituents, meeting the community’s actual needs and wants, and representing the organization’s mission to community members, stakeholders, and employees in a way that makes sense. And as she did in the Peace Corps, she’s very much returning to her roots: she first engaged with the organization when she was growing up in New York. “They served me as a high-school student, so now I’m serving them,” she comments.

As she looks to the future, Magassa is applying to graduate programs. She says she wants to “combine media communications with data [and] using data as means to understanding what communities want”—especially those communities in which “individuals are deprived of rights, opportunities, and resources.” But as she reflects on her time in the Peace Corps as well as at Southwestern, her advice to others who might follow a similar path applies whether they’re applying to college, deciding on what organizations to join, or applying to the Peace Corps or other postgraduate opportunities: talk to multiple individuals to gain a range of perspectives on their experiences, be prepared to be uncomfortable, build trust and relationships within the community, and, perhaps above all, “be open. I can’t stress how open you need to be. Just be ready for anything to happen, and be positive.”