News

Our Shared Humanity

July 26, 2019

July 26, 2019

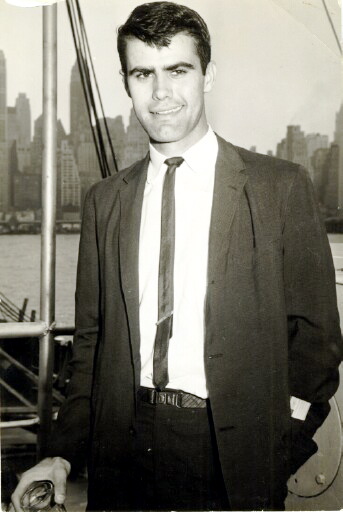

Darrel Young ’61 can tell you how John F. Kennedy shook hands: one hand grasping, one presidential hand warmly covering yours.

Just eight months before he found himself meeting the American president in the East Room of the White House, Young had been an English major at Southwestern University who was planning to attend law school at the University of Texas at Austin (UT). While walking through what was then SU’s student union, Young was captivated by the “intelligent speech” and “elegant words” as well as “the compelling cadence and Irish tenor” of JFK’s voice as the new president delivered his inaugural address—yes, that one, the one quoted on posters, echoed in speeches, and taught in civics classrooms for decades to come.

The Peace Corps (PC) did not yet exist for JFK to mention it during his inaugural speech, but Young felt inspired by the president’s “calling us beyond ourselves, challenging us to relate to the world in ways that made life sound so well worth living.” So when Kennedy issued Executive Order 10924 on March 1, 1961, establishing a new agency that aimed to provide “assistance to nations and areas of the world” and to promote international and intercultural understanding, Young heeded the call. He sent in his application that same month, and in June 1961, he received a telegram and then a letter from Robert Sargent Shriver Jr., Kennedy’s brother-in-law as well as the driving force behind and director of the new agency, accepting him for service. Young looked up Colombia, South America, where he was being assigned, on a map—“I didn’t have any idea of where Colombia was!” he admits with a hearty laugh—and soon accepted his place among the first wave of PC volunteers.

In was in September that Young found himself face to face with the man who had inspired him to serve his country. It was a brief moment, maybe 10–15 seconds, but as the SU graduate clasped hands with JFK, Young saw what so many Americans saw in those early years of the 1960s: that the president was a “transcendent charmer” who knew how to connect with young people and, perhaps more significantly, who trusted these first PC recruits to carry out what he saw as a crucial mission. Namely, JFK believed that these bright, motivated 20-somethings could successfully effect change where American foreign policy had failed. “He told us we were important people, we were going to do important work, and it was important for the world to know the United States,” Young recalls. With his confident smile and one hand tucked into his jacket pocket, the president told the members of Colombia One to “be prepared to use your resources and do good things around the world, … in keeping with our shared humanity.”

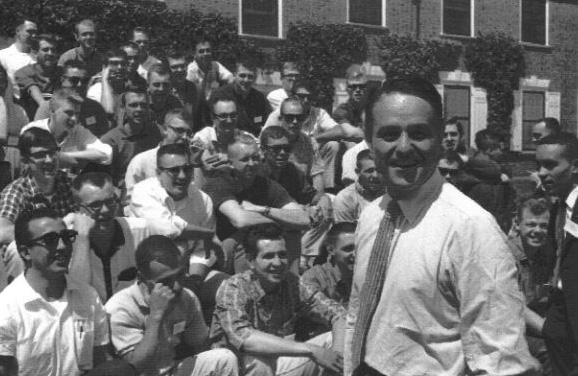

The “mountain men” of Colombia One

The training that preceded the meeting with JFK involved grueling endurance tests aimed at preparing the PC volunteers for the physical, mental, and emotional rigors of being so far out of their comfort zones. Young recalls being expected to hold his breath while swimming the length of an Olympic pool (50 meters, or 164 feet)—for you Texans, that’s almost half the length of a football field.

“And of course, your immediate and predominant thought is, ‘That’s not going to happen!’” Young laughs.

Diving in was a freeing and ecstatic experience, he says, but approximately 20 meters in, your lungs would begin to burn. “Your body is going to start saying, ‘Surface! Surface! I need air! This is a foreign element!’” Young continues. “It develops into something of a panic point in your body.” But the PC trainers encouraged them to not give in, to keep pushing through, stroke by stroke, until the panic subsided and they reached their end goal—or at least close to it.

Young believes that such lessons were not just apt training for the Peace Corps but also for life more generally: “People who opt out at the first panic point live rather limited lives in some sense. … If you stay with it [and] move through it, you’re going to find that you can do much more, and the rewards are so much greater on the other side. So that’s what the swimming was all about: they were trying to get you into it and to develop [your] confidence that you could weather the bad times and do much more than you thought when you were in the depths of despair and diarrhea.”

“People who opt out at the first panic point live rather limited lives in some sense. … If you stay with it [and] move through it, you’re going to find that you can do much more, and the rewards are so much greater on the other side.”

While swimming and learning how to ride horses in the U.S., the PC volunteers took coursework with anthropologists and spoke with journalists. These scholars and experts explained that Colombia had been in the throes of political violence and civil war for the previous 13 years. During La Violencia, 200,000–300,000 lives were lost, 600,000–800,000 were injured, and nearly 1 million were displaced during battles between paramilitary forces and militias, peasant-on-peasant massacres, en masse rape, horrifying torture sessions, and assassinations by machete-wielding bandits. But the Colombia One volunteers remained undeterred; they were buoyed by optimism and a desire for adventure.

So when they landed in the wee morning hours, in Bogotá, the capital of Colombia, Young and his fellow mountain men were unperturbed by the contingent greeting them, which included U.S. Embassy representatives, Colombian officials, and a battalion of soldiers sporting combat uniforms and brandishing automatic weapons.

Community development

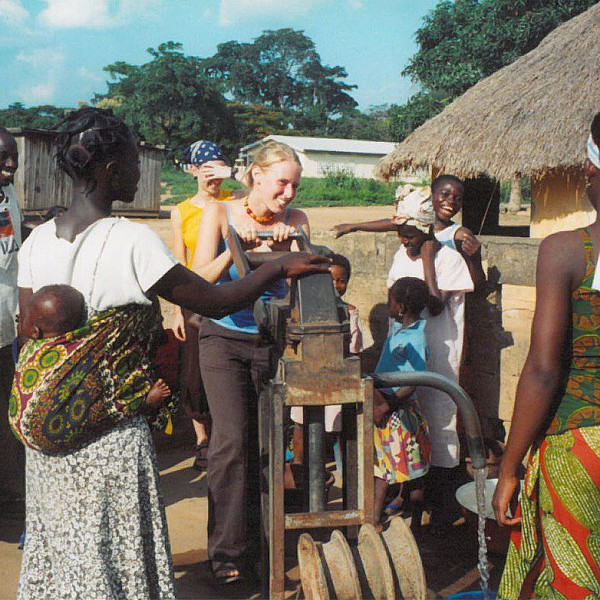

The volunteers would spend five more weeks of training acclimating on site; then, they were sent in pairs to surrounding towns and villages throughout the region, tasked with supporting community development—or, as Young puts it jocosely, “go to a foreign country, stand up in front of some strange people, and use your broken language to motivate them to undertake local self-help projects.”

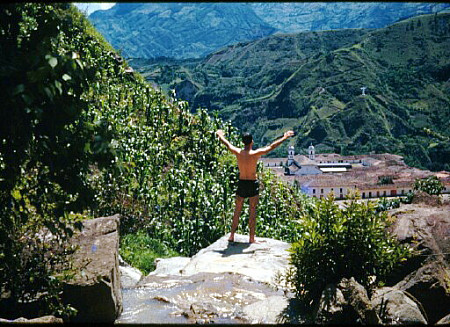

Young traveled with his partner, fellow PC volunteer Rick Jaspersen, to San Pablo, a town ensconced in the Colombian Andes in the southwestern Nariño Department (i.e., state). This mountainous region was coffee-growing country; Colombia vacillates between being the world’s second- and third-largest producer of the rich, flavorful beans. So although the Colombia One volunteers were working under the auspices of the new community-development agency Acción Comunal, they were also supported by the Federación Nacional de Cafeteros de Colombia (the National Federation of Coffee Growers of Colombia), a wealthy, powerful nonprofit business association of more than 500,000 coffee farmers that promotes production and exportation of the crop (if you’re familiar with the Juan Valdez character used in coffee ads from the 1970s to today, then you are at least somewhat familiar with the Cafeteros’ reach). Young and Jaspersen’s Colombian counterpart, Aurelio Muñoz, was employed by the Federation.

“We lived in a little three-block-square village that had maybe 900 people living there,” Young recalls, not to mention the squealing pigs and squawking chickens that would constantly run in and out of residents’ homes. “It was very remote, and it was off the main road—no phones, no newspaper, no mail, no cars,” he says. “You were really cut off from everything.” The houses were rudimentary at best, with dirt floors and a makeshift fireplace for cooking. “Everyone, including the volunteers, smelled like wood smoke all the time,” he reminisces. “And there wasn’t any running water.”

In the absence of other vehicles, one enterprising local man had somehow acquired and outfitted a flatbed truck with a canvas awning and backless benches. So once a month or so, Young, Jaspersen, Muñoz, and officials who had been elected from their partner communities would be driven six to seven hours to the state capital of Pasto to meet with members of Acción Comunal, Public Health, and the Coffee Federation to help secure equipment and materials for various projects.

The project spanned more than a year, but when they gathered to give the aqueduct its trial run and the water flowed freely , PC volunteers and local residents alike cheered in jubilation. Reflecting on the official dedication of the historic project, Young remembered a tidbit from his PC training: “Development is change in people.” He saw a newfound confidence in the people of El Chilcal, triumphant in their achievement but also motivated to continue developing their community. “I’m in a strange land with strange people, yet I am strangely at home,” Young wrote in WorldView Magazine. “At some level, I joined the Peace Corps to save the world, and on this night, saving the world seems definitely doable.”

On not saving the world

Of course, as generations of volunteers will tell you, individual members of the Peace Corps are not exactly saving the world. It can feel like that sometimes, certainly, as Young did on that day and night of celebration in El Chilcal. However, volunteers will also reveal that the Peace Corps teaches you some rather hard lessons—about the difficulties of supporting global and community progress, about the ugly side of human–parasite relations, about their own limits and motivations.

Not a week after the elated celebration of the aqueduct, the National Federation of Coffee Growers withdrew their support from community-action projects, meaning they would no longer partner with Acción Comunal; instead, the Federation preferred to carry out projects themselves, only perfunctorily consulting local residents and bringing in their own labor crews to complete the work. Young believes this happened because the Federation didn’t want community members to become more confident and feel empowered; instead, they preferred to treat rural residents as charity cases who would show deference for rather than ownership of the development projects in their settlements. In effect, it was the opposite approach to that of the Peace Corps.

Without the Federation’s cooperation, the PC volunteers’ service became much more difficult. However, they continued to collaborate with communities to raise money and implement their projects, such as building schools and bringing electrical power to villages. “Turns out I didn’t save the world,” Young shares, “but I was part of people asserting themselves more within their own world, and after two years, I let it be at that.”

Sacrificing the self to connect with others

All the while, Young was building relationships with community members—relationships that are often built on partaking in food prepared by locals. “Most of the food didn’t taste too bad,” he comments. “But some of it wasn’t all that good, either,” he snickers. “But you do the PC thing: you swallow hard and smile. Because once in, you’re trying to connect with people, and you don’t connect by not saying ‘yes’ and ‘thank you.’ But as a consequence, I got all sorts of bugs.”

There’s no way to put this gently: for months, Young endured bouts of diarrhea. He lost 10–12 pounds in a matter of four to five days, and his clothing was hanging off him. His skin and eyes had also begun to yellow. He was suffering from jaundice, a symptom of the viral liver disease hepatitis A, which is highly contagious. The infection, which also causes fatigue and flu-like symptoms, is transmitted by consuming contaminated food or water or, as Young puts it bluntly, “literally eating s#*%.”

Around six to seven months into his service, Young was sent to a hospital for a battery of psychological and medical tests. When the doctor called him in to share the results, the physician pointed to a one- or two-foot-tall chart on the wall. “You see all these parasites?” the doctor asked. “You have every single one of them.” So Young was prescribed a month-long regimen of drugs—“8, 10, or 12 pills a day,” he recollects—and eventually got back to work. His then girlfriend, now wife Barbara Smith Young ’63 reports that even two months after he was released from the hospital, when she met him in Mexico City during his vacation, Young still “looked horrible” and “was skinny as a rail … and still kind of yellow.”

By the way, if you’ve never had the pleasure of playing host to intestinal viruses and other parasites, you should know they are, apparently, fairly tenacious little creatures: almost 30 years later, after Young was subjected to another array of medical tests and even some exploratory surgery, another doctor would confess that he initially thought his patient was suffering from stomach cancer. But instead, he diagnosed, “It’s all parasites. And it looks like it’s been there for a long time.” Young reassures me that another big drug cocktail helped him get over his symptoms. Then, he chuckles, “So, you know, I gave my GI tract for my country. … You have to be willing to sacrifice something of yourself if you’re actually going to be able to connect with others.”

Culture shock and despair

That ability to connect with local residents helped the members of Colombia One and the volunteers who served during the decades that followed to overcome those panic points—those moments of stress, frustration, anxiety, and/or depression—that can plague PC volunteers. “I think it lessens the degree of culture shock when there’s some sort of relationship there,” Young says. “I went through a humongous culture shock. The first couple to three months, it’s all novel; it’s new; it’s interesting. But then, at some point three to four months in, you sort of fall off the cliff. Suddenly, all those things become repulsive. It’s like going off to college magnified by 20 times.”

During that period, Young experienced a despair that many Southwestern–PC alumni will echo: a desire to hole up in his own room for the remainder of his two years of service. A PC volunteer’s mind goes to ominous places during those panic points, places that can understandably elicit dark humor: “When I was in the depths of culture shock, I never got to the point that I wished my mother would die, but I got to the point that my mother would get gravely ill so I’d have an honorable way out,” Young laughs. “That’s the sort of frame of mind you get into: you don’t want to give up, but you want an honorable way out.”

Multiple PC volunteers can confirm this way of thinking. But it’s only by pushing through that feeling of vulnerability and isolation and by eventually making the choice and effort to interact with the community that the benefits come into play. “One guy said that the first year [of his PC service] took five years off his life and the second year added 10 years to it,” Young shares. “You really have to overcome your own ego. When my ego was flattened, that’s when people really started educating me. … When you’re involved more, that’s when you really start to learn so much. And all the insights are so enriching. You learn so much about yourself, about others, about the country and your own country, about the world and the universe. It just opens up a whole side to you.”

After completing his service and returning to the U.S., Young took up the path he’d originally planned before applying to the Peace Corps: he enrolled in law school at UT. But he had already begun to question that decision while living in Colombia, and while attending classes, he confirmed that “it just didn’t speak to me: I like justice, but I don’t care much for advocacy or being a gun for hire.” So he went to work for the State Department for three years, studying at the Foreign Service Institute and learning Vietnamese before spending two years in the rural provinces of Vietnam. By then, traveling abroad and living in remote areas was far less of a struggle. He then returned to Texas to Corpus Christi, near his hometown of Kingsville, where he worked for Westinghouse and in politics for four or five years before he decided to return to UT to pursue a Ph.D.

“Some part of my soul, my being, whatever, became Latinized in those two years, so I wanted to get back in touch with South and Latin America,” Young recalls, “and developmental economics seemed to be the way to do that.” He completed his doctorate, and in the mid-1970s, he won a prestigious Fulbright scholarship that took him, Barbara, and their young children to Lima, Peru, where they lived for a glorious year. Young then was offered a teaching position in Puebla, just southeast of Mexico City, and would serve as dean of the business school there until the Mexican economy collapsed after the debt crisis of 1982. Young and his family repatriated to the U.S., where he would continue teaching Latin American economics at UT Austin until he retired in 2001.

The PC experience still very much resonates with Young and the first-wavers. Because of their collaboration, Acción Communal expanded, as did government and community investment in development in Colombia. Since their return in 1963, members of Colombia One have reminisced during reunion events, written articles and even a book on their adventures, and delivered talks about their memories. Young even designed a T-shirt bearing a U.S. flag comprising the names of his fellow volunteers, which he proudly sported when we met for our interview in Austin this past spring.

“Peace Corps is very transformative, and I know the people who do it still find it transformative.”

“Peace Corps is very transformative, and I know the people who do it still find it transformative,” he says. To current Southwestern students considering a volunteer commitment after graduation, Young has no qualms about encouraging them to apply. “If the idea appeals to you, do it,” he urges. “You’ll get in touch with those parts of yourself that you never knew existed. It’ll serve you well. Peace Corps makes you more. You see the world through the eyes of the Other. You see more, you feel more, you understand more, and you are more ever after. If that resonates with you, Peace Corps is for you.”