News

Art History Mystery, Part 2

July 30, 2019

July 30, 2019

See part 1 here.

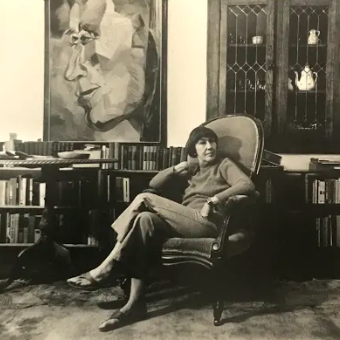

Elizabeth Tracy Montminy painted her controversial mural, Bathers, in the Kennebunkport, Maine, post office in the summer and fall of 1941. Buttoned-down citizens made snide comments while the artist worked; high-powered statesman complained that her depiction of “fat women, scantily clad, disporting themselves on the beach” was objectionable. And so, through an act of Congress signed by President Harry S. Truman no less, the artist’s vibrant artwork was removed—and subsequently vanished. Had it been destroyed? Had it been moved to an archive for preservation and safekeeping?

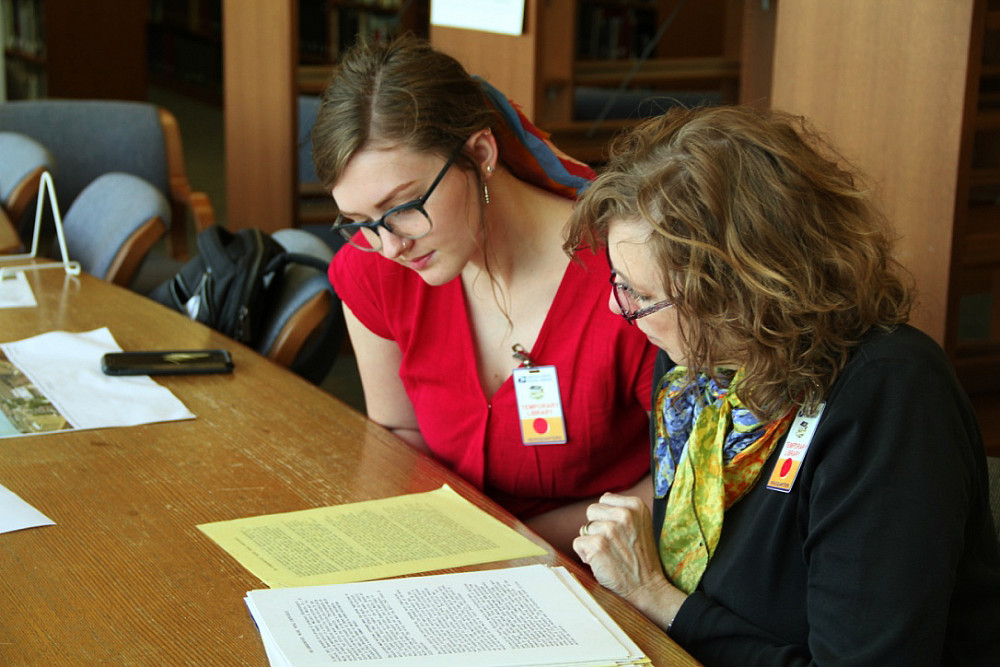

This past May, a former student of Montminy’s, Southwestern Professor of Studio Art Victoria Star Varner, and three of Varner’s own students, recent graduates Sophia Anthony ’19, Kati Hellmer ’19, and Danbi Heo ’19, embarked on a quest for the missing mural that would take them across the country.

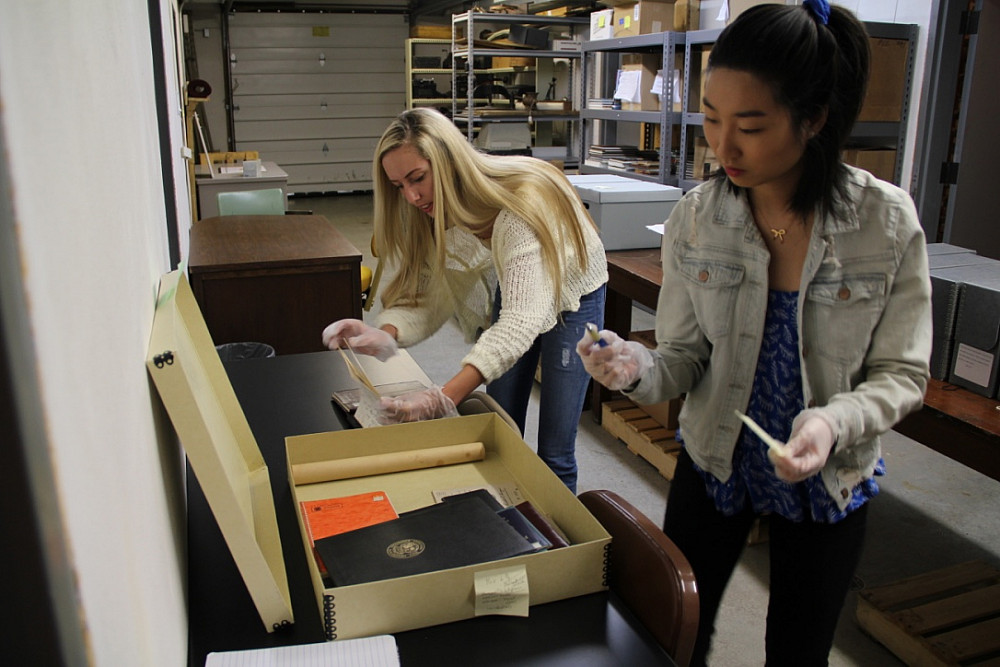

The 10-day research trip began at the Boone County History and Culture Center, in Columbia, Missouri. The red-roofed museum houses the Boone County Historical Society as well as the Montminy Art Gallery, a nearly 3,000-square-foot exhibit space that the artist endowed upon her death in 1992 for the safekeeping of her work as well as that of her husband Pierre Montminy, who had also been an artist and college professor. Today, the gallery and the museum’s storage facility contain just some of the Montminys’ murals, oil paintings, drawings, and sketches, so the Southwestern detectives thought it the perfect starting point for their search.

Anthony says that the Boone archives were “the most exciting because they had so much information” about the artist, and Heo loved seeing how Montminy’s painting style evolved over the decades. Varner appreciates that they were allowed “full access,” including to uncatalogued documents. She and her students found a large number of photographs of Montminy and her family as well as some of her notebooks, poetry, and correspondence. For example, they encountered a succinct letter, dating from 1982, written by the artist and addressed to the editor of the New York Times Book Review. In it, Montminy disparages her time painting in Kennebunkport decades earlier: “I spent several miserable months on a scaffold in the Post Office listening to scathing remarks.” But according to Anthony and Heo, that brief epistle was the only trace of the missing mural that they discovered.

The criticisms that helped bring down Montminy’s mural included that by local author Kenneth Roberts, who commented sarcastically that the mural’s colors must have been “slapped on with a shingle” from a “hog wallow”—meaning a muddy shallow trench where pigs can roll about. “It may be imagination, but a fragrance of the hog wallow has always seemed to me to cling to the picture,” he continued savagely.

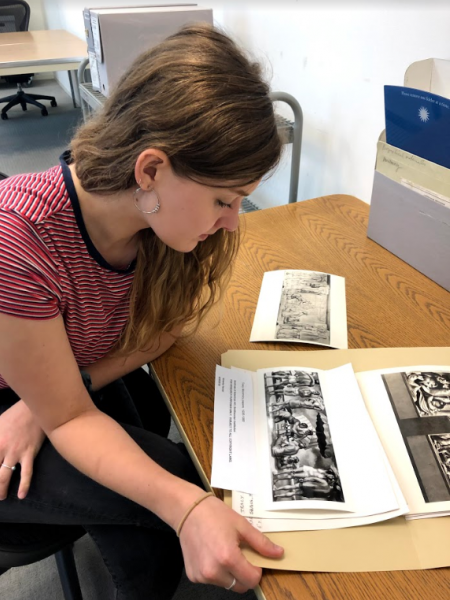

In DC, Varner and her collaborators also discovered a report for a government organization with the cumbersome moniker the Fine Arts Inventory Public Buildings Service General Services Administration (GSA). The document would seemingly deliver a blow to the Southwestern team’s investigation. In the May 24, 1972, report, Richard West, then director of the Bowdoin College Museum of Art, described Kennebunkport Harbor in 1825, the oil painting that replaced Montminy’s Bathers. His inventory included the following ominous note: “Mural presently in place replaces one originally painted by Elizabeth Tracy [Montminy], for the Federal Works Agency. Its style & subject matter (bathers on the beach) raised such an outcry that local residents (including Kenneth Roberts & Booth Tarkington) took up a collection ($1,000) to commission a new mural from Gordon Grant. The original was destroyed during removal and mounting of new mural.”

“The original was destroyed”: One might think that the disappointing end to the search. However, West’s report contradicts that of Edward Rowan, the operational deputy of the U.S. Treasury Department’s Section of Fine Arts—the very agency that had originally commissioned Montminy’s work. According to a letter dated May 21, 1945, soon after the mural was removed, Rowan claimed that the artwork “has been carefully taken from the wall and is in the safe custody of this office.” He continued, “It is my hope that I may find a suitable space for it in a building in which its fine qualities are appreciated and where there is no question whatsoever, relative to the appropriateness of the subject matter.” So there was still hope; perhaps the mural had survived?

Varner and her students discovered evidence in the Smithsonian archives that the quest for the missing mural continued nearly 50 years later. “We found some letters asking about where the mural was, so Montminy herself didn’t know,” Heo recounts. For example, they learned that the GSA had looked for misplaced artwork in their storage facilities during the 1970s, but their search had turned up no 1930s- or 1940s-era murals. In 1988, in response to requests from the artist, the Office of the Postmaster General, the General Services Administration, and the Treasury Department attempted to locate the mural again—but in vain. The researchers also encountered a short missive of April 1991 penned by Joyce Butler, the curator of manuscripts at the Brick Store Museum in Kennebunk, Maine, and addressed to the Office of the Postmaster General. Butler wrote, “Thank you for taking the time you have for us. We, at least, are now ready to concede defeat, but do keep us in mind if some day you find this ill-fated piece of art hanging in a forgotten corridor.” In other words, the search ended in frustration—but not without hope.

Continuing on where their predecessors had left off, the Southwestern artist–researchers proceeded with the investigation. The final leg of their journey took them to the site of the Montminy mural itself and its disappearance: Kennebunkport, Maine. Varner says that it was “very useful to be in the post office to see the replacement mural”—Gordon Grant’s shipbuilding painting that citizens from nearby Kennbunk were critical of because it lacked historical accuracy. (One begins to wonder whether any mural would have satisfied the locals.) The researchers also consulted with Kirsten Camp, the executive administrator of the Kennebunkport Historical Society, who helped the artist-detectives understand more about the history of the people in the local area and further context for the mural controversy.

The researchers then visited Goose Rocks Beach, where Montminy had depicted her titular Bathers. There, Varner photographed Anthony, Hellmer, and Heo emulating the poses of the figures in Montminy’s mural, which Varner plans to piece together into a video depicting an artful dance. “It was cold. It was very cold,” Heo remembers. “My ears were ringing. I don’t know how it would be in July during the time period she was painting, but I definitely wouldn’t wear a bathing suit there!” she giggles. Varner adds with a quiet smile, “Yes, I don’t imagine there are too many bathers out there.”

Ultimately, the researchers’ fast-paced hunt for Montminy’s missing mural ended without the team locating the much-sought-after artwork. The Bathers, it seems, continues to elude those who seek it.

But the story does not end there. After all, Varner, Anthony, Hellmer, and Heo’s quest comes at a time when citizens, critics, lawmakers, and scholars are debating about the placement and preservation of public artworks that are part of the historical narrative but that ignite controversy given their potentially offensive content. But in the midst of others advocating or decrying the removal of Confederate statues and debating about the covering of Depression-era murals adorning the walls of a San Francisco high school that depict potentially objectionable scenes from the life of George Washington, Varner and her team of student artists still hope to recover the scandalous Montminy mural—in one way or another.

Stay tuned for the final installment of our “Art History Mystery” to learn where the case of the missing mural leads. Meanwhile, Varner encourages others to report any information they find about the missing Montminy mural to her atvarnervs@southwestern.edu. This project is funded by a competitive faculty-development grant and friends of Sarofim School of Fine Arts.