Public Engagement

Uncovering Community Through Music: Florence Price and Margaret Bonds

Only recently have the careers of Florence Price and Margaret Bonds been highlighted through the work of Dr. Michael Cooper, Professor of Music at Southwestern University. Dr. Cooper works to help preserve culture by bringing these composers’ legacies back into the light of the world.

November 24, 2025

November 24, 2025

Open gallery

While classical music is integral to the lives and development of so many, we often only hear about the white, male composers. They are not the only musical people of innovative talent; there is an entire world of individuals who have been silenced. Dr. Michael Cooper, a Professor of Music at the Sarofim School of Fine Arts at Southwestern University, dedicates his life to the research and publishing of particular artists, in hopes of raising their voices to an equal academic and musical level as those already known. His main focus are the careers of Florence Price and Margaret Bonds, two African American women and composers in the mid-twentieth century. I sat down with Dr. Cooper and discussed his contributions to academia, specifically addressing his publishing of the works of these women who have dedicated their lives to their art, breaking molds throughout their careers.

Florence Price and Margaret Bonds are two highly significant figures in the musical sphere.

Price, born in 1887 or 1888 in Little Rock, Arkansas, dedicated her life to the perfection of the piano, completing two diplomas by the age of 19 and teaching in various forms across the South. Bonds, born in 1913, began studying piano at an early age, and once she reached the age of just 8 years old, she began studying at the Coleridge-Taylor Music School. At this school, her musical journey overlapped with Florence Price, and she studied with her for some time. She graduated from Northwestern University with her Bachelors and Masters in music performance, and continued to write and perform brilliant music for the rest of her career.

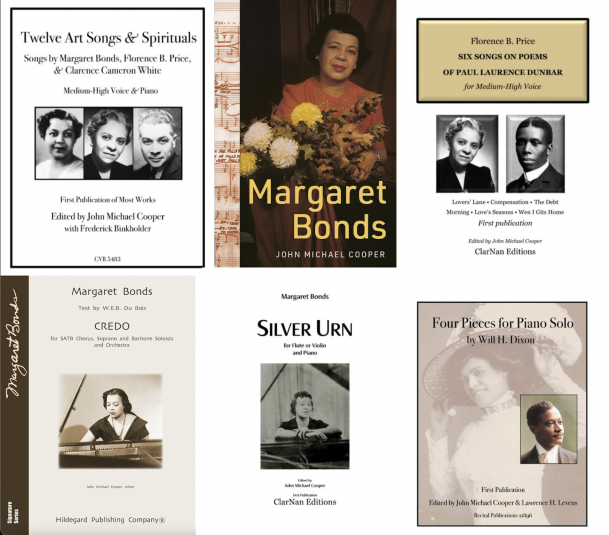

Only recently have their careers been highlighted through the work of Dr. Cooper. Earlier this year, he published an entire book on Margaret Bonds. He continues to publish hundreds of pieces from Price, Bonds, and composers alike, emphasizing that this is simply work that must be done—it’s important that we keep focused on Bonds and Price, not on their latter-day advocates.

Dr. Cooper works to help preserve culture by bringing these composers’ legacies back into the light of the world. Bringing them to higher education is in of itself a work of activism, teaching about these composers alongside, equal to, and sometimes instead of canonical white men like Beethoven and Bach, whose biographies and music are familiar and easily accessible anyway.

INTERVIEW:

How do you see bringing this art back to life as a valuable resource in regards to connecting to other people?

Dr. Cooper: Margaret Bonds, Florence Price, Clarence Cameron White, all of these distinguished African American composers—many of them women—created their music not just as an act of expression [but] as an act of communication for people to consume, to discourse, to make part of the fabrics of their own life. As long as those pieces they wrote are consigned to the archives, those utterances are silenced, suppressed. And we, the public and the performers and scholars who let it remain silenced, are affirming society’s marginalization and silencing of their voices. So in a sense, the project of publishing their many unknown works so that others can perform and study them is just a matter of stepping aside so that the music can be heard.

And what I have observed happening from performances, the recordings, the comments, and the publications, is that those who engage with this music invariably find themselves thinking about the things that Bonds, Price, and their contemporaries talked about in that music. It really is an act of social discourse. Not for everybody—some people are there to be entertained rather than to think about what they’re hearing—but performers and audience members listen carefully and closely. Those people will take the message of those songs with them. So it is remarkable: those voices of people long dead and impossibly remote from our own world are able to start conversations among us, today.

I was wondering about your work getting the community involved, and further that if we are just at least getting it out there, there’s importance in that. We are giving voice to not just the artists but their pieces. For example, it’s amazing to see how we took SU Chorale and the Austin Civic Orchestra to perform Bonds’ “Credo”, and a full house of people showed up. Everyone was insanely moved, and that is the hightlight of my musical career at college.

Dr. Cooper: Someone in the chorale described it to me as a ‘life changing/altering experience’ and that of course is exactly what you want. That said, the Bonds’ “Credo” is a work like no other. We have a lot of “sacred texts” in the world of Classical music, like Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, Mahler’s Second Symphony, and other works by Bach, Mozart, etc. Those works are “sacred texts” in the sense that they have been sacralized and they have this vaunted status where their authority has long since gone unquestioned, and we ‘dare not’ challenge it.

But those pieces, compared to the Bonds “Credo”, are just assemblages of platitudes. There’s no other piece of classical music that speaks truth to power so eloquently and fearlessly. Yet Bonds’s voice was silenced until quite recently, while the music of Bach, Mozart, and other white Euro-American male composers is hailed as profound and essential.

With me singing Bonds pieces right now, I don’t know anything like these three early songs and I think it is a life changing experience as a performer to work with these songs…this is challenging in the way that not many have sung this before so you have to do it justice, which is something in and of itself.

Dr. Cooper: Acclaim and success are correlative to familiarity, so people repeatedly perform pieces that are already familiar rather than new ones. That’s a great way to affirm what the familiar pieces say and an equally great way to suppress what those pieces don’t say. A lot of people don’t realize the latter point. So part of the importance of you singing these early songs, even though they are not as ‘direct’ or ‘forceful’ as the Credo, is that every piece of music has its own beauty, its own message that is otherwise unheard in our world today. Thank you for taking them on.

How do you enact public engagement with this work? Where are performances taking place? Are these performances drawing audiences that would otherwise not go or are there more listeners than usual?

Dr. Cooper: They’re being performed all over the United States and Europe. That is of course vastly more performances than has happened previously. In Price’s case, it’s been about 72 years since she died, and in Bonds’ case it’s been about a half century. In these cases those works have gone from near-zero for most works to dozens of performances reaching many times that many listeners.

I hope many more performers will take them up as eagerly as one might expect. Every single one of these pieces is a worthy peer of the pieces by Bonds and Price that are already known…they’re wonderful and amazing pieces.

Journalists and program annotators like to tell the dramatic stories of much of Bonds’s music being left beside a dumpster and missing the landfill by a matter of hours, or of a young (white) couple finding a trove of Price’s compositions in an abandoned house. But if we’re going to make a big deal of those stories (which are true, by the way), we have an obligation also to make a big deal of the works that were saved: the music is the point. That’s of course easier said than done. As you’ve seen yourself, it’s difficult to be the first – to perform a piece that hasn’t already been recorded, for which there are no models. It’s a MUCH bigger artistic task than doing something that has been recorded 396,000 times! But that doesn’t mean you shouldn’t do it—it means you should do it.This is your chance to sing their unsung songs, to advocate for them.So I’m thrilled that you’re singing them.

I believe it will accelerate […] I know that [performances] have happened in every state of the union and I know of five commercial CDs that are in preparation right now by all kinds of artists.

The way that the internet works with making things popular and trending is so weird, and you can’t really be a ‘proper’ musician, in my opinion, these days. Something has to go viral and it’ll move forward from there. But that’s why I think working with the Office of Public Engagement is so important, because we are trying to bring awareness to so many things, but physically, in person, not making it go viral on the internet. Just bringing community together and word of mouth.

Dr. Cooper: Frustrating, right? Unfortunately, streaming platforms often identify the title of the work and the performer but not the composer. That’s based on the popular music model, where songs are considered to belong to performers. But it works against Florence Price and Margaret Bonds if people are searching for their music by composer’s name. If something that we’re doing is trying to engage people by means of the composer’s name and the composer is left out of it, then the internet is actually continuing the suppression.

[…]

The most important part of the work I do is simply not continuing the suppression. My students all know Florence Price and Margaret Bonds, they know Langston Hughes; they know the names of these and other great historically suppressed musical and poetic voices from my classes. Those voices are just a part of the musical landscape, and whether those people are aspiring professional musicians or just music interested, or just [required to take a Fine Arts course], Florence Price and Margaret Bonds are included in what they know about music rather than excluded from itThat is something. It doesn’t change the world, but it might change somebody’s life or heart a little bit.

It doesn’t necessarily change the world but it changes those people, and those people can be the people to change the world.

Dr. Cooper: That’s always the hope. Just as a general principle, you can teach music history and the world of music with those composers or without them. I choose the former. It’s just that simple.

Have you seen a difference in response to music pieces in general now that you are highlighting women of color? I think the answer has already been given, which is not yet, but you want it to be.

Dr. Cooper: I’m seeing some difference, but it’s not happening on the scale I would like. I think the turning point may be the point where these professionally produced commercial CDs/albums come out. That’s a different level of authority that is afforded to those pieces, [and] they’re all coming out at about the same time.

Do you know when they’re coming out?

Dr. Cooper: It should be early 2026. That is what everybody is shooting for.

Would you say that SU’s music department is properly engaged with that work and do you think that the music department in general is properly publicly engaged, and does that have anything to do with the work you present?

Dr. Cooper: While it is true that the music department, especially Dr. Julia Taylor and Katherine Altobello are certainly doing their part [with] these pieces being included in the pedagogy of their vocal studios, [I believe there is more work to be done]. But Music is a much smaller department at SU than it was even ten years ago, and the same thing goes for the Fine Arts – our resources for doing this work and our reach are much smaller than they need to be (I can’t tell you how much I appreciate being able to talk about these composers in this venue). We’re doing what we can, but unless our colleagues pay attention, the difference we can make is limited.

END INTERVIEW

Dr. Cooper’s research has not only engaged with the community, but unveiled the community and life of artists who were previously silenced. He informed me during our interview that five CDs will be released come early in 2026. His hope is for their popularity to grow exponentially from there, and for them to get the recognition they deserve.

His work to preserve their intentions and legacies will continue on, and Southwestern has the chance to be front and center in a movement to right the wrongs of marginalization in the past and open new pathways for our own community and others, or to revert to the status quo and continue rehearsing the same status quo that, for all its merits, can no longer purport to be of our world or address itself to our world’s needs. Dr. Cooper’s students are choosing the former, and he hopes others will do the same.