News

Full STEAM Ahead

July 13, 2021

July 13, 2021

When you ask recent SU graduate Lauren Muskara ’21 about almost any aspect of her college career—the story of how she changed her majors and minors, her experiences as a site leader and student director with the community-engaged learning program Breakaway, her research into apple snails and environmental DNA, her leadership of the biology honor society Beta Beta Beta, her science-informed oil paintings, her award-winning interdisciplinary projects, her winning the Vicente D. Villa Award in Ecology and Evolutionary Biology and the Lancaster Award in Studio Art—the words tumble out of her mouth excitedly, and she has to catch herself to take a breath.

She personifies genuine and infectious enthusiasm about learning.

“I’m a very passionate individual,” she declares. “I love everything I do, which makes it difficult because there are so many different things I want to dedicate my time to [that] it’s hard to be selective.” Fortunately, one reason Muskara was drawn to Southwestern was that she knew it would allow her to explore different opportunities to “leave an imprint” while connecting her seemingly disparate interests. “If you have lots of passions, there is a way to meld everything you love doing!” she says.

Double the major, double the fun

The daughter of a breast cancer survivor, Muskara arrived at Southwestern as a biology major on the premed track. While attending high school in Plano, she had seen her mother undergo a double mastectomy and breast reconstruction, and Muskara was inspired by how plastic surgery combined sculpture and medicine, shaping the human body like molding clay. Having always cherished a love for both science and art, she decided she had found her path.

The young biologist enjoyed her coursework in the natural sciences first semester, but by the spring of 2017, something definitely felt lacking. “I’ve been involved in art as long as I can remember,” Muskara shares, and taking her first formal painting class at SU helped her realize how much she was missing time in the studio. Her instructor at the time, Kristen Van Patten, encouraged her to major in art or pursue it as a career.

But she soon realized she didn’t have to choose; she could truly integrate her passions.

Muskara decided to alter her career pathway and briefly switched majors from biology so that she could use her undergraduate years to specialize in painting. But she soon realized she didn’t have to choose; she could truly integrate her passions. “I came to the right place,” she says. “One of the reasons I chose Southwestern was the ideals of Paideia, so after my freshman year, I said, ‘I’ll double major. I’m going to do both. It’s going to be great!’”

What does integrative learning look like?

Some might assume that Muskara’s choice to pursue such apparently unrelated majors meant splitting her educational path, as if she were bouncing constantly between two parallel roads toward graduation. However, with the support and encouragement of her faculty mentors, Muskara accomplished what Paideia had promised her: the ability to intersect art and science—to make chemicals intersect with canvas, to make art out of apple snails.

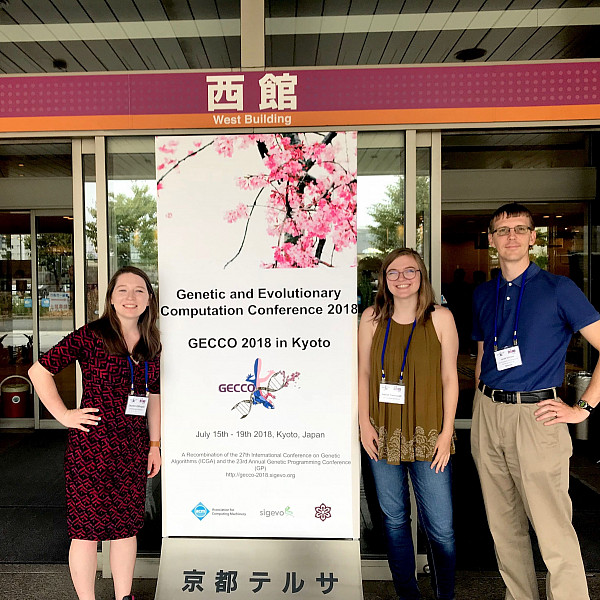

In 2018, she began conducting research through the Summer Collaborative Opportunities and Experiences (SCOPE) program in the molecular ecology lab led by Professor of Biology Romi Lynn Burks. Her team studied how to use environmental DNA (eDNA) to detect the presence of a nonnative invasive species, Pomacea maculata, commonly referred to as apple snails—an experience she says “has been a huge influence”—and Muskara got to present that research at various conventions, including a national conference in Salt Lake City, Utah, in summer 2019. Just a couple months earlier, at Southwestern’s 2019 Research and Creative Works Symposium, she exhibited Shared Genetics, a remarkable artwork on linen depicting guanine and cytosine, two of the chemical bases of DNA. Muskara ground hair taken from three generations of her family into the oil paint to create the intersectional piece. The following year, she depicted the apple snail of her molecular ecology research and expanded her Shared Genetics piece into Exploring Relationships: The Art of Science, a project she completed under the direction of Professor of Art Victoria Star Varner. It won Muskara both a King Creativity grant and the 2020 King Creativity Fund Walt Potter Award.

Muskara used the King Creativity grant to purchase supplies to complete her Exploring Relationships series, and she is grateful that she gets to continue using those supplies today while working as an artist outside the formal studio setting. The Walt Potter Award helped her purchase a subscription to Adobe Creative Cloud; “I am teaching myself those programs to enter the digital world,” she says. She has been able to use those applications to create materials for Southwestern’s chapter of the TriBeta biology honor society and to design BioScope, a newsletter produced by the SU Biology Department. She also applied her new digital illustration skills to the SciArt project she and her classmates completed in fall 2020 to educate audiences about COVID-19 and raise money to support Southwestern students in need. “I was so thankful for that, too,” she reflects, “because it was the perfect Paideia moment: using this Walt Potter prize to help fund this SciArt project to raise money for the SU Emergency Fund.”

“it was the perfect Paideia moment: using this Walt Potter prize to help fund this SciArt project to raise money for the SU Emergency Fund.”

While interlacing materiality with molecules, Muskara constantly strives for both “aesthetic rigor”—the ability to, for example, distinguish her work as a piece of fine art and not simply a textbook illustration—and sufficient technical accuracy so that a scientist would still recognize what she has rendered on canvas. “A lot of my inspiration depends on what I’m focusing on in the science world at the time,” she explains. “My research heavily influences my art.”

Making STEAM education more inclusive

Earning two degrees—both a bachelor of arts in studio art and a bachelor of science in biology—in addition to minoring in health studies and earning Paideia with Distinction required Muskara to add a fifth year to her college plan. But she is grateful that Southwestern offers flexibility in its curriculum and that her parents were supportive of her taking the extra time to explore and connect her many intertwined passions. For example, she felt compelled to add to her dual majors a minor in health studies, which she found “fascinating” because it complements courses in the natural sciences with offerings in the social sciences, humanities, or fine arts. “I love how Drawing II is considered part of health studies!” she says enthusiastically. “I took that and Comparative Vertebrate Morphology in the same semester, so I was able to draw morphological parallels between species, looking at the anatomy of organisms and understanding the human body through different lenses.”

The interdisciplinary minor also enabled Muskara to take seminars she would not have expected to enroll in otherwise. “I never thought I’d take an education class like Survey of Exceptionalities with Dr. [Alicia] Moore even though I love learning so much!” she remarks. “That class changed my outlook because we talked about visible and invisible disabilities, the education system and how it supports and lacks support for neurodiverse, neurotypical, and other students.”

That new outlook unexpectedly shaped Muskara’s postgraduate plans, too. This summer, she began pursuing a master of science in biomedical visualization from the University of Illinois at Chicago, where she will continue to combine her interdisciplinary interests by exploring interactive media—such as augmented reality and virtual reality—as well as 3-D modeling, animation, medical–legal applications, and scientific or medical illustration. (Her familiarity with the graduate program, she shares, is also a result of the Walt Potter Award: the funding allowed her to purchase a student membership with the Association of Medical Illustrators, through which she networked with professionals who work in her current field.) Muskara is not certain what she will do after her master’s degree just yet. She could, for example, pursue anaplastology, a medical field in which professionals develop prostheses for lost facial features, such as eyes or ears, and body parts, such as fingers and limbs. “It’s a combination of painting, sculpture, medicine, and science, and some people are 3-D printing now, so technology is integrated, which is a prime example of how cutting-edge technology continues to influence the field,” she explains. “It sounds amazing!” Or she could end up educating patients by developing interactive games or animations, training physicians or veterinarians by designing medical devices or models, or working in biotech or medical software development.

“My overarching goal is to make STEAM [science, technology, engineering, art, and math] education more inclusive by bringing that interactive element into education, whether it’s K–12 or college.”

Whatever profession she chooses, she says, “My overarching goal is to make STEAM [science, technology, engineering, art, and math] education more inclusive by bringing that interactive element into education, whether it’s K–12 or college. Too many times, I’ve encountered people who say, ‘I can’t do math’ or ‘I can’t do science.’ But it’s not that you can’t do it; it’s not being presented in a format that is accessible to your learning style. I’m pursuing the graduate program I’m in now because I have the opportunity to make STEAM education more accessible, and that’s a topic we discussed formally in that [education] class I’d never even planned to take.”

One of Muskara’s goals, then, is to improve the educational environment by introducing interactive technology, such as augmented or virtual reality, so that more students can learn successfully and feel more confident and motivated in especially their science classes. To talk with her is to have no doubt that she’ll achieve her objective. Still, it’s hard to imagine anyone being as ebullient about everything they do as Muskara is. “You can’t have STEM without the STEAM to create and develop and innovate,” she asserts with a winning smile. “That’s why I love King Creativity and Southwestern: they’re really pushing those barriers.”