News

Keeping a Pandemic at Bay

Staff work overtime to keep the Pirate community safe during COVID-19.

June 03, 2021

June 03, 2021

Open gallery

It was an inauspicious end to Rick Martinez’s first day on staff at Southwestern University. The school was a few weeks away from spring break. That afternoon, he attended a meeting of the emergency management team where, huddled close around a conference table, they discussed a virus that was still mainly an issue in China but beginning to impact certain regions of the U.S.

“Within two weeks, there was a drastic change from the day I started,” Martinez says.

Martinez had previously worked up the road at the Belton Independent School District, but in March 2020, he began his new job as the associate vice president for facilities management at Southwestern. As spring break began and students headed off to South Padre for vacation, Martinez turned on the TV and saw nonstop coverage of the pandemic and other universities deciding to close their campuses.

New York, the initial epicenter of the COVID-19 crisis in the U.S., was just beginning its lockdown. The rest of the country, epidemiologists determined, was a week behind New York. Back at SU, administrators decided to extend the break for a week. Then, they canceled the students’ return to campus entirely.

“After spring break, everybody realized that this is going to be a long, drawn-out process,” Martinez recalls. “I don’t want to say it, but it hit the fan.”

“The great pivot”

In every department, Southwestern employees began preparing for a job they never signed up for: working on the frontlines of the university’s response to a global pandemic. Because of interdepartmental cooperation and SU’s size, which allowed the university to pivot to confront the newest challenges, Southwestern has been able to provide an on-campus experience for students while also keeping them safe.

In every department, Southwestern employees began preparing for a job they never signed up for: working on the frontlines of the university’s response to a global pandemic.

Scarlett Moss, chief marketing and communications officer and vice president for integrated communications, immediately began spearheading the communications effort. Her team collaborated with other offices to develop informational videos and keep the website and social media updated. Behind the scenes, they reached out to experts, epidemiologists, public-health workers, and alumni to get information about the disease.

This was trial by fire for Moss, who started her employment at Southwestern in January 2020 after years of working in corporate communications at Coca-Cola.

“I can honestly say that in all of my years in the corporate world … a pandemic as widespread as this was never drilled,” says Moss.

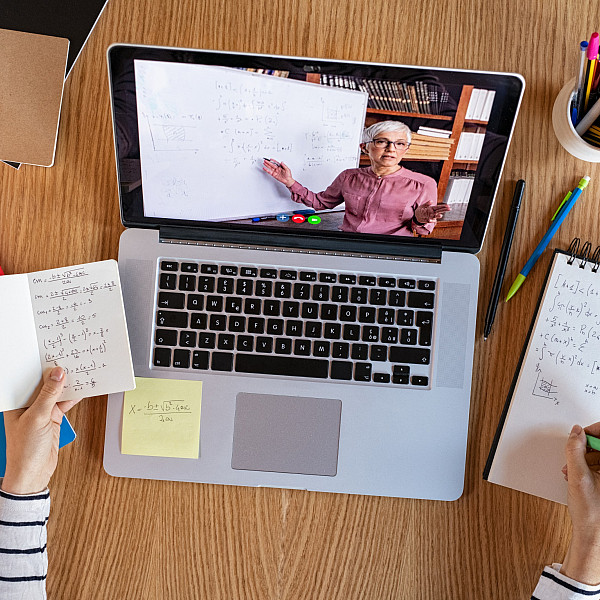

Daryl Tschoepe, director of technical support and services, refers to the beginning of the pandemic, when the university went fully remote, as “the great pivot.”

“In tech support, you could’ve heard a pin drop,” he shares. “Oh gosh, I’m remembering the horror of that now.”

The great pivot drastically altered daily life in Information Technology, which Tschoepe says normally did “a lot of hand-holding”: logging people on to their computers, fixing a projector when a panicked professor called. Now, his team was a crucial link in the transition to remote learning with a staff that previously relied entirely on in-person meetings.

“Yesterday, somebody called the help desk complaining because their VPN connection wasn’t working,” says Tschoepe. “Turned out her husband was playing with the Wi-Fi and had turned her laptop connection off.”

Still, although they still experienced technological difficulties, staff members learned to evolve.

“If you’d told me that was going to happen a year ago, I’d say, ‘Yeah, I think that’s about the time I retire,’” remarks Dave Seiler, director of academic success and a self-identified “dinosaur” when technology was involved. He compares RingCentral and Zoom meetings to The Brady Bunch intro but says working virtually allowed his office to be more empathetic to students, and he sometimes schedules check-ins later in the evening to accommodate schedules.

In the Office of Student Activities, director Derek Timourian tried to offer virtual programming in the spring, such as trivia nights and quarantine concerts. “Initially, we were just stumped,” he says. “It felt like you were trying to write that term paper: … you were literally looking at a blank sheet of paper, wondering what you were going to do.”

A frenzied summer

In December 2018, Jennifer Spiller, family nurse practitioner and health services manager at Southwestern, met with Williamson County health officials about the possibility of using the university as an emergency mass vaccination or antibiotic center in the case of bioterrorism or an outbreak of deadly diseases like tuberculosis or anthrax.

“We had plans for that sort of emergency protocol, but not something where we really didn’t have a treatment,” Spiller reveals.

She spent the summer setting up the Pirate Assessment Triage and Containment Hub (PATCH) in Moody–Shearn Hall, where students would go for same-day polymerase chain reaction testing or if they had COVID-19 symptoms. The PATCH operated separately from the Health Center in Prothro, so students who might test positive for COVID-19 were in a separate location. Spiller prepared to split her time between the Health Center and the PATCH, where she would wear an N95 mask, face shield, and gloves when seeing patients.

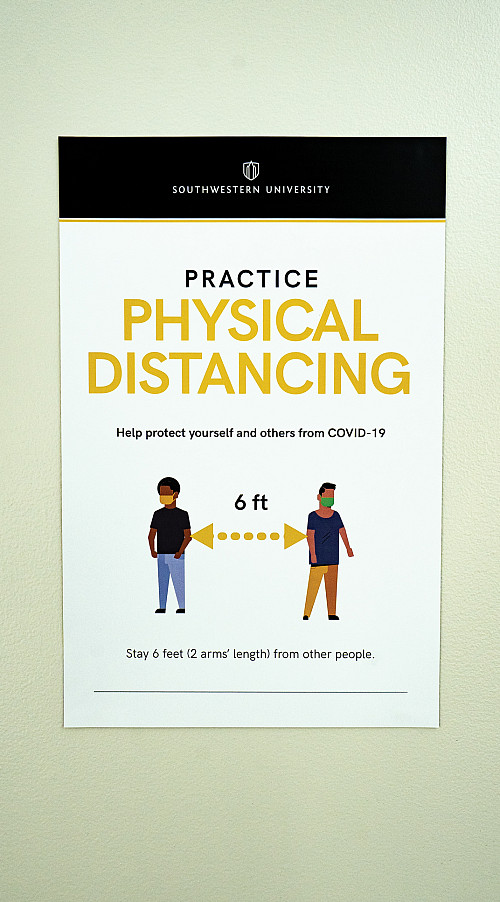

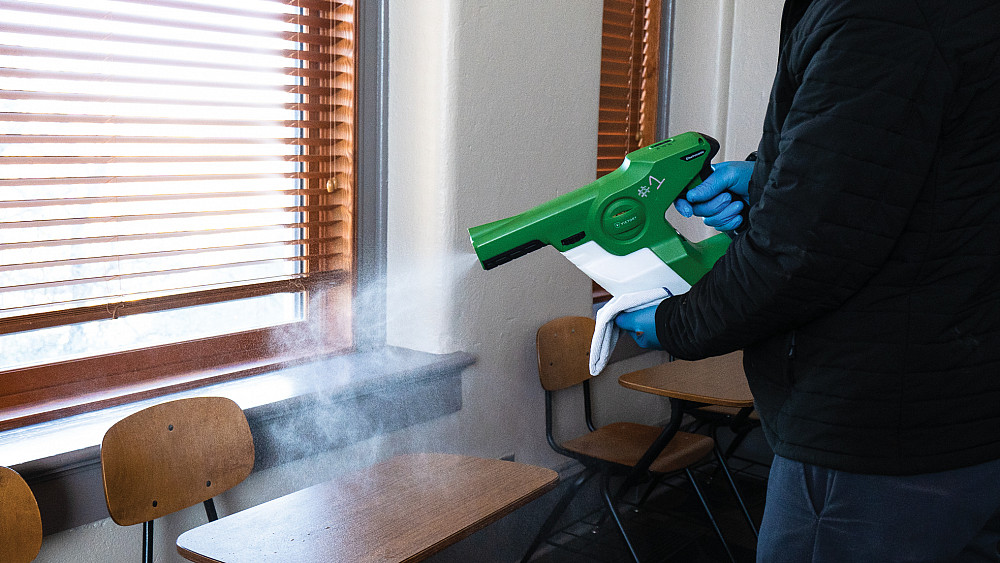

Facilities Management, in full force with a day shift and an evening shift, began decontaminating classrooms and common areas. In classrooms, the team spaced desks six feet apart. To accommodate new social-distancing protocols, the McCombs Ballrooms and even the basketball courts were transformed into classrooms. Air filtration was upgraded, and plexiglass barriers were installed in high-traffic areas. Disinfectant and hand sanitizer stations were placed in all the classrooms, and yellow arrows directed the flow of traffic.

Randy Erben, manager of facilities services, equipped his team with full personal protective equipment: Tyvek suits, masks, gloves, and shoe covers. Facilities worked with Residence Life to prepare rooms for quarantine. Meanwhile, Tschoepe in tech support worked on equipping the classrooms with screens, projectors, and sound systems for remote learning.

Like other staff members, Tschoepe had workshopped disasters occurring, but nothing like a pandemic. “It’s usually hurricanes, tornadoes … you’re talking about a short period of time,” he says.

Departments that normally functioned separately began planning together. Just before the pandemic started, the Facilities Management team had been in the process of purchasing a new disinfecting system using ultra-soft water and a weak hypochlorous acid. The team worked with a member of the chemistry faculty and the university’s safety manager to vet the product, which turned out to be capable of killing SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19.

Departments that normally functioned separately began planning together.

In July, disparate departments joined forces and held table-top meetings, where members played out scenarios: What if there’s an outbreak at a frat house? What if someone tests positive after a sporting event?

“Some of those were pretty ridiculous,” recounts Seiler, from academic success. “Everyone will giggle and laugh and say, ‘That’s not going to happen.’ But sure enough, something similar to it happened, and we had to be ready.”

The university asked existing employees to double up on their duties and become care coordinators and contact tracers for the cases that would inevitably occur once students returned. Contact tracers enrolled during the summer in a virtual training offered by Johns Hopkins University and practiced talking to students over the phone and telling them they needed to quarantine.

The staff spent the summer working strenuously to get the campus ready for when students returned after Labor Day. Now, their teamwork and the skills they had so diligently learned—heightened communications, working remotely, contact tracing, deep cleaning, and increased technical support—would be put to the test.

A fall to remember

Timourian, who had found it difficult to hold student activities remotely during the spring 2020 semester, was now determined to make it work.

One casualty of the virus was Pirate Training, the orientation for incoming first-years, in which hundreds of students would gather in the gym, sitting on the bleachers and splitting into teams for activities. Timourian shifted the program from Pirate Training to Pirate Quest, a virtual scavenger hunt through an app. Teams of four or five students used Google Earth to explore Georgetown and find landmarks such as the Monument Cafe or completed tasks on video, like a trick-shot challenge in which, as Timourian describes, “they would drop stuff out of the third floor of Mabee and catch it in a trash can on the ground.”

Other events were reimagined. For the Annual Greek Chili Cook-Off, instead of squeezing students into Bishops’ Lounge, students created cooking videos in their residence halls and apartments, and judges critiqued the videos instead of sampling the chili. Student Activities also hosted a virtual escape room, a Super Smash Bros. tournament, and a painting event in which students picked up supplies and made art in their dorms,

“We’re just trying to remind the students that this, too, shall pass eventually”

“We’re just trying to remind the students that this, too, shall pass eventually… . It’s easier for the older generation to see this as a transient period that we will get through,” says Timourian, who has worked at Southwestern for 28 years.

A culture of care

Once students arrived, the Health Center continued rigorous testing, each week selecting 50 people randomly from the students, faculty, and staff and screening them at the PATCH.

When Southwestern eventually had outbreaks of COVID-19, the preparation and teamwork among the staff ensured that the quarantine and contact-tracing process went smoothly.

If a student chose to quarantine on campus, they would move into a room in the Lord Center or Brown–Cody Hall, where each bedroom had a separate ventilation system and bathroom, to isolate for 14 days. The custodial team would immediately decontaminate their room. While in isolation, they would get meals delivered and their trash picked up, and if they ran out of clothes, Athletics staff would wash their laundry.

The care coordinators, such as Xan Koonce, who regularly works as the associate director of university events, would contact the student who tested positive and interview them, determining if they were symptomatic and building a list of who they were in close contact with. The care coordinators would then give this list to the contact tracers, who would ask those people another set of questions and alert them that they needed to quarantine.

“There were several moments that it was intense,” Koonce shares. “There were times where they had a lot of close contacts, several times where we had to quarantine a fraternity house … . There’s a lot at stake when you’re trying to keep a pandemic at bay.”

Koonce, like many others during the pandemic, is doubling up on her professional duties. On top of contact tracing, as an event planner, she’s organizing two socially distant commencement ceremonies on the same day at the end of the spring semester: one for the class of 2020 and one for the class of 2021.

The university’s health and safety protocols continue as the crisis wears on. When discussing the pandemic that has irreversibly changed everyone’s life, it’s hard to keep positive. A dose of cynicism seems like a self-defense mechanism. But this isn’t the case when speaking with Southwestern staff members, some of whom contributed to this article while quarantined after a close encounter with the coronavirus. Many staff members have been going into the office just as much as they did before the pandemic, risking themselves because they believe in providing a safe environment for the education of Southwestern students. But no one takes all the credit. Instead, they divide it among their hardworking teams and their colleagues in other departments who they’ve gotten to know better, connecting to each other even in this dark time and proving that when everyone works together, they can overcome even the most difficult of challenges.