News

It’s Just Not the Same, Part 3

May 14, 2020

May 14, 2020

Open gallery

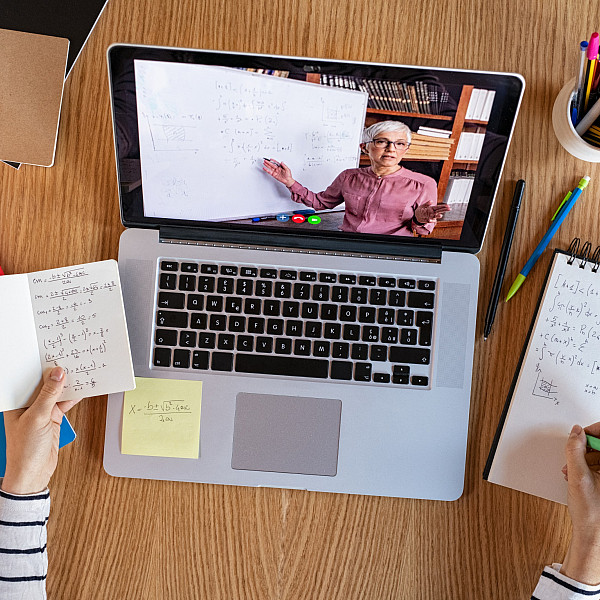

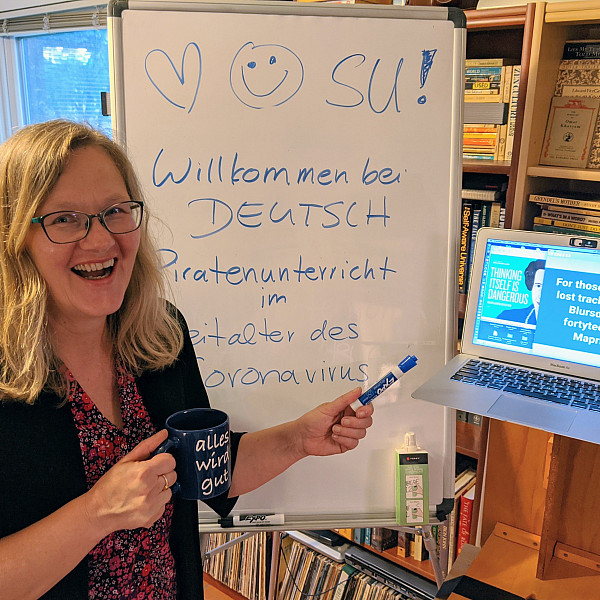

Getting creative

As they prepared faculty for the transition to remote learning, one reassuring message Julie Sievers, director of the Center for Teaching, Learning, and Scholarship, and Melanie Hoag, instructional technologist, wanted to convey to professors was that “this isn’t really a time for innovation,” as Sievers says. Most faculty and students were already susceptible to stress and anxiety having to learn and get comfortable with new online tools—think, for instance, of how many of us have fumbled with just making sure microphones were turned on during a Google or Zoom meeting. “Melanie and I have been urging people to adopt the simplest tools and strategies possible to reduce the cognitive load both for themselves and for their students,” Sievers remarks.

Hoag agrees. But, she adds, they have both observed “innovation and creativity [in] what the faculty have done and are continuing to do to provide the best experiences for their students.” The faculty have also demonstrated their signature commitment to helping students connect across disciplines, beyond the classroom, and to the local and global community.

In her Advanced Biochemistry Lab, for example, Maha Zewail-Foote’s students were in the midst of an independent project and could not complete their research in the lab once stay-at-home orders went into effect. So, she explains, “I created assignments that still taught the students how to design experiments, troubleshoot, and summarize data, but I also wanted students to use this opportunity to make a difference during this difficult time.”

For one such project, students were given the freedom to come up with a project that would help others, such as tutoring students who were now being homeschooled or producing videos to teach children science while they are at home, including the myths and truths about the novel coronavirus. In her Biochemistry of Nucleic Acids, meanwhile, the students switched gears by learning about the biochemistry of SARS-CoV-2 (the virus) and COVID-19 (the disease), compiling as many questions as they could conjure: How is it transmitted? How does it recognize a receptor? How does the virus replicate? What biochemical tests, vaccines, and therapeutics might there be for the disease? The students researched answers in the current scholarship, just as they would when conducting a literature review for any scientific question, and shared their discoveries with one another.

As it has been for faculty teaching science labs, making the shift to online learning poses particular challenges to those teaching studio art. Ron Geibel, a creative in that he’s an assistant professor of art who specializes in ceramics and design, had to get even more creative with how he was facilitating his studio courses given the issue of access to materials for drawing, painting, and sculpture—although the same would apply, he adds, “even if I was teaching a design course.” His more advanced students are familiar with how to set up a safe work environment, and a few of his seniors were able to take clays home with them and continue to work, but younger students might not be as versed in, for example, how to properly ventilate their spaces to avoid the noxious fumes wafting from the solvents used to dilute oil paint or clean brushes. And even advanced students might not have the resources to create safe home studios, nor did Geibel want to put extra pressure on any of his students by asking them to continue making at home with so many limitations.

Still, he says, “they could still be learning about form and color, even though the main component—the material—is missing.” So his beginning Ceramics: Hand-Forming class is posting asynchronous responses to excerpts of documentaries that he’s curated about how different cultures across the world and throughout history have approached and appreciated ceramics. His senior seminar, meanwhile, is meeting weekly to discuss assigned readings on materiality and crafts theory as well as videos produced by the Ceramic Materials Workshop that introduce viewers to the properties and engineering of clays and glazes. Both groups have been invited to join Geibel in sharing relevant images of artwork on Instagram group chats—because, he explains, it’s a platform that has changed art significantly in the past 10 years, but also because “it’s a good way for me to see what they’re looking at, … and I wanted to use social media in a way that they’re already doing so it doesn’t feel like extra work.”

In addition, Geibel’s seniors are researching and writing proposals for art projects and exhibitions that they unfortunately will not get to make—at least not until they again have access to studios, even if that means sometime after graduation. Nevertheless, articulating the objectives, plans, and significance of their visions and designs is an important skill for artists to practice considering that proposals are crucial in applying for funding or for exhibition space. So although his students aren’t necessarily creating in the sense of making art, they are engaging in significant creative projects as well as “really great conversations” and even “heated debates” about the creative arts.

Associate Professor of History Jess Hower had to reimagine an assignment in her History of the British Isles since 1688 course that she looks forward to every time the seminar is offered: an in-class debate, worth 10% of each student’s final grade, in which her students recreate parliamentary arguments made in spring 1886 for and against the First Home Rule Bill, a proposed law granting Ireland self-autonomy and independence from the United Kingdom. Students are assigned to one team or the other, prepare by reading numerous primary and secondary sources on each side of the debate, and then spend a class period engaged in fierce formal debate before closing with a postmortem in which they discuss which side they truly thought had the strongest argument.

Hower says that the event “is so energetic” and “is such an exciting moment,” and it’s also a crucial piece of students’ understanding of the history of Ireland’s role in the British Isles—“it’s an opportunity for students to embody and empathize with history,” she explains. She also couldn’t bear to disappoint the students who enrolled in the seminar partly because of this particular assignment. So when Southwestern converted to distance learning, she knew she couldn’t replicate the debate environment, but she also couldn’t just omit the experience entirely. She asked her students to prepare as they normally would, but instead of an in-class dialogue, the students would engage in an asynchronous debate in Google Docs, asserting and rebutting claims during a 48-hour period. All 25 students participated, eventually creating a 32-page single-spaced document. “It was sophisticated, it was scholarly, and they were engaging with the material. It was awesome!” she recalls proudly. “That was also the Monday we started virtual teaching, so I thought, ‘Maybe we can get through this.’”

“It was sophisticated, it was scholarly, and they were engaging with the material. It was awesome!”

Even digital natives can find remote learning challenging

Although current students at Southwestern are part of the multigenerational group known as digital natives, not all have found the transition to remote learning easy. It’s not that students struggle so much with navigating videoconferences or Moodle—many, after all, are more comfortable with the technology than their professors are. Rather, for many SU students, getting and maintaining access to high-quality Internet service has been a struggle—a concern one might expect from those living in rural areas but has nevertheless been echoed by those living in urban and suburban neighborhoods, where many household members at a time might be competing for bandwidth and large populations of people working from home are experiencing areawide outages thanks to overwhelmed service providers.

“Some of them are struggling with access to technology,” Associate Professor of Psychology Erin Crockett ’05 shares. One of her students, for instance, has a dial-up connection, so whenever Zoom freezes up during a class session, the student has to call in. Others are working on computers that are not equipped with cameras, so they, too, have been calling into classes and using their smartphones to share their screens.

But one of the most difficult obstacles that their students are having to overcome are the rollercoaster of emotions this semester has elicited: the shock of having to suddenly move out of the residence halls; the sadness of not having more frequent interaction with friends; the stress of losing on- or off-campus jobs or knowing that loved ones have been furloughed or laid off; the annoyance or frustration of readjusting to living with one’s family after months or years of independence at college (or else the strain of enduring toxic family environments or unstable living arrangements); the frustration of trying to homeschool or help homeschool children or younger siblings; the boredom of not having internships, jobs, athletics, or other cocurricular activities to fill their evenings and weekends; and the fear of the unknown in the face of a worldwide public-health crisis that is anxiety provoking enough in the abstract but downright traumatic when a loved one has been infected with the virus, is on a ventilator in an ICU, or has lost their life to COVID-19.

Many students, however, have adapted as well as they can—with success—and their professors are grateful. “To be honest, none of this would have been remotely possible without these two particular groups,” Hower says of the students in her History of the British Isles and Witches, Nuns, Prostitutes, Wives, and Queens seminars. “It’s like I hand-picked the perfect combination of students who could not only face the challenges that we’re dealing with but also embrace them and commit to doing their best. If they weren’t game—if they weren’t willing or responsive to me—then I’d be lost. My groups are amazing, and that has been the key to all of it.”

Crockett describes her students as “doing brilliantly,” and she’s proud of what they’re accomplishing in the midst of such challenging circumstances. “Nobody wanted this, no one asked for this, [and] most of us didn’t even expect this, so getting to a place where we can say, ‘But given this is what it is, how can we move forward?’ has been a productive conversation to have with them.” She adds that for especially SU seniors, she’s collaborating with colleagues to brainstorm some sort of online celebration that will provide the closure they need and deserve. “It’s important to have that time to say goodbye and mark an ending to something that was really meaningful for them,” she says.

Zewail-Foote sees her students’ resilience as evidence of a Southwestern education. “Change can be difficult, but learning how to adapt will be a lesson we all take away from this situation,” she argues. “This is a scary time, but this is also a learning moment on so many levels. A liberal-arts education is not just about learning course content. Now, more than ever, is the time to learn how to handle difficult situations, how to grow as individuals, and how to move forward.”

In the concluding installment of this series, SU professors will reflect on the highs and lows of remote teaching this spring as well as the potential impacts of this experience on their face-to-face courses later this fall.