News

Rediscovering a 20th-Century Musical Master

February 25, 2019

February 25, 2019

Open gallery

A musical pioneer

In 1933, Arkansas native Florence Price (1897–1953), a pioneer among black female concert music composers, became the first African-American woman to have a large-scale composition performed by a major American orchestra. Her Symphony in E Minor was performed by the Chicago Symphony Orchestra on June 15 as the cynosure of the World’s Fair. Price’s inclusion in the Century of Progress International Exhibition was remarkable for the times: African Americans were denied service at restaurants at the exposition, and throughout the United States, African Americans and especially African-American women had to enter establishments through separate doors and drink out of separate water fountains. Perhaps not surprisingly, then, although she had been the rare black female student to graduate from the New England Conservatory of Music in Boston, Massachusetts, and was a prominent member of the Harlem Renaissance along with W. E. B. Du Bois and Langston Hughes, Price was relegated to relative obscurity soon after her death.

However, Professor of Music and Margarett Root Brown Chair in Fine Arts Michael Cooper is one of the growing number of scholars who are working to restore Price to her rightful place in the canon of 20th-century American concert music. Over the past several months, Cooper has been researching, editing, and coordinating performances—some of them world premieres—of previously unpublished Price manuscripts. “She was an incredibly important composer during her lifetime,” Cooper says. “She had her music played by no fewer than 11 major orchestras, which is something that any composer today would be happy to claim. She became a cultural institution in Chicago, which is one of the music capitals of the United States. So the question is not one of discovery but rediscovery—and why she was so aggressively written out of so many mainstream music-history textbooks. … The fact that an African-American woman was able to pull off a creative and stylistic synthesis that was transgressive of social, political, and musical norms and achieve such remarkable renown in doing so—only to be written out of history books as soon as she died—is something that is profoundly instructive but also disturbing.”

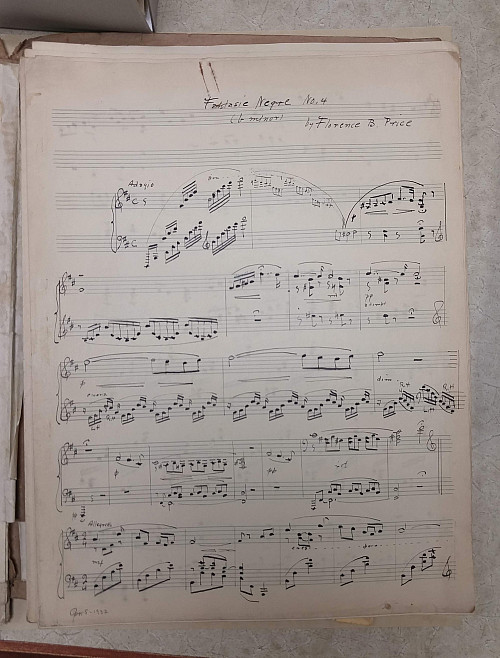

Credit: Florence B. Price Papers (MC 988b), box 4A, folder 1. Special Collections, University of Arkansas Libraries, Fayetteville.

The tip of an archival iceberg

Cooper was familiar with Price when he first came upon what was at the time the most complete inventory of her music in a 2010 book chapter on concert music of the Harlem Renaissance, which is a topic Cooper has been fascinated with and studying for 30 years. “This has to be just the tip of an iceberg,” he thought, so he began compiling an inventory the following year that included far more of Price’s manuscripts than had been previously listed. Then, this past spring, among the archives of the composer’s manuscripts collected by the University of Arkansas, in Fayetteville, Cooper found himself surrounded by thousands and thousands of pages of Price’s tidy musical notations. “I think that it’s probably somewhere on the order of 100 linear feet of papers, plus many more pages in other archives,” Cooper recalls.

But in addition to the voluminous size of the collection, Cooper was surprised at the intersectionality and stylistic diversity he found among Price’s compositions. “I expected to find a lot of influences of jazz, blues, and spirituals because that’s what [audiences] had already heard by her,” he remarks, “but I found other pieces that she and her contemporaries would have regarded as highly unusual for African-American composers and transgressive of her very conservative training at the New England Conservatory. And she did these pieces with extraordinary fluency and brilliance.” Integrating European concert music or progressive avant-garde elements with spirituals, blues, or jazz, Price was “obviously experimenting with that goal which of course was a huge part of the Harlem Renaissance, the Chicago black renaissance, and all of those movements that eventually led towards the Civil Rights movement: that impulse toward freedom of personal expression. [Price] wanted to be who she was and say whatever she wanted to say in her music. And nothing that I had seen or heard discussed about Price or any of the music that I had heard performed prepared me for how stylistically diverse her work would be.”

The size of the archive is attributable to Price collecting and organizing her work for posterity. But “even though she published a number of pieces during her lifetime, she was interested in having them performed more than publishing,” Cooper says. That’s why when Southwestern Visiting Assistant Professor of Music Beth Everett first announced that her first concert at Southwestern would be on the theme of night, Cooper approached her with the notion of performing one of the Price compositions he had discovered, edited, and published. Everett happily agreed. Price’s piece, written for a women’s chorus with piano, is a setting of “Night Is Like an Avalanche,” a poem by Bessie Mayle, published in a 1930 issue of The Crisis, the journal of the NAACP. Price’s “Night” first premiered in Chicago in 1945, but it enjoyed its modern world premiere at the November 3, 2018, concert of the Southwestern University Chorale.

A resonant—if surprising—complexity

“It’s just a remarkable piece even though it’s only about three minutes long,” Cooper says admiringly. Price’s originality lies in her ability to melodiously blend seemingly incongruent associations: Mayle’s poem depicts the complicated issue of asserting racial pride against the backdrop of black oppression and exploitation, but Price unexpectedly sets those provocative words to the soothing strains of a lullaby. Price’s composition was most likely written for an amateur choir in Chicago, and “for a young African American in Chicago’s Southside in the 1940s, the experience of singing these particular words with this lovely music would have been an unexpectedly and wonderfully beautiful and affirmative one.” Cooper suggests. “I think that’s how she achieved her resonance in those times: she had this extraordinary ability to connect, in ways both subtle and striking, to the issues of the world that surrounded her.”

Since the spring of 2018, Cooper has edited 72 of Price’s manuscripts, meaning he clarifies ambiguities in and typesets each composition for ease of reading by today’s musicians. “This is a very significant scholarly achievement,” says Director of Teaching, Learning, and Scholarship Julie Sievers. “Michael is doing original archival and scholarly work that is at the leading edge of national efforts to bring to light a significant composer who has historically been understudied and underperformed.”

Meanwhile, Cooper’s joy in the work is evident: “It’s a wonderful process because [even] without having the musical imagination to create it, you’re still engaging with putting the notes on the paper, so you hear this music in a way that nobody ever hears it, one note at a time, one syllable at a time.” He also remains enthralled by Price’s ingenuity and continues to champion her accomplishments. Her compositions are “extraordinary,” Cooper says, “but there’s also the question of how the musical world will now deal with the process of continuing to get to know her music.” Over the past several decades, various textbooks on 20th-century music of the United States have written a narrative that excluded Florence Price. “What I and a lot of other people are doing is to ask not what that [history] looks like without her,” he says, “but what it looks like with her. And the answer will change the picture.” And in the meantime, he’ll continue offering his editions of Price’s work to choruses. “My goal is to have the music performed, to have her voice in musical life again,” Cooper says. “If I can help that to happen, then I’ll be happy.”