News

Patience, Grit, and an Open Mind

Lauren Gillespie ’19 reflects on what it takes to research, present, and publish successfully as a chemistry and computer science double major.

January 22, 2019

January 22, 2019

Lauren Gillespie ’19 is a STEM student par excellence. She’s a chemistry and computer science double major. In 2016, she was one of the few sophomores admitted to SCOPE, one of Southwestern’s undergraduate research programs, in which she tested artificial-intelligence agents in video games with Assistant Professor of Computer Science Jacob Schrum. This past October, she received an Undergraduate Student Poster Presentation Award in Computer and Information Sciences for her project with Schrum and Gabriela Gonzalez ’16, “Comparing Direct and Indirect Encodings Using Both Raw and Hand-Designed Features in Tetris,” at the 2018 National Diversity in STEM conference organized by the Society for Advancement of Chicanos/Hispanics and Native Americans in Science. And most recently, evolved animations generated by AnimationBreeder, a program that Gillespie developed with fellow senior Isabel Tweraser ’19 and Schrum, were featured as the cover art for the latest issue of SIGEVOlution, a newsletter on genetic and evolutionary computation.

Most of us without science degrees would have trouble even parsing the titles of those various scholarly projects, but Gillespie describes her research with the ease of a seasoned expert. So it might surprise you to learn that one of Gillespie’s favorite classes at Southwestern was Comparative Politics with Professor of Political Science Eric Selbin. “It was a nice break from STEM. It had a completely different format from most of my other classes because it was very discussion oriented,” Gillespie recalls. “The thought process in the course was different, and Dr. Selbin himself was very much into opening up our minds.”

Keeping an open mind and being willing to inhabit diverse perspectives are just a couple of the characteristics Gillespie believes are key to being successful at Southwestern—and to majoring in two rigorous STEM fields.

Keeping an open mind and being willing to inhabit diverse perspectives are just a couple of the characteristics Gillespie believes are key to being successful at Southwestern—and to majoring in two rigorous STEM fields. “A lot of that interdisciplinary stuff that SU lives and breathes is really so important for successful research, for success in computer science, and especially in technology,” she says. “It’s very easy to get into the mindset that you just need to know how to program x languages. You might be really good at cranking out code, but to really ideate something new or make those new connections and get around a roadblock, you need an open mind to think of different areas of research.” As with Selbin’s politics course, Gillespie advises taking advantage of SU’s Paideia® approach to education, exploring disciplines that might not immediately seem applicable to your interests or majors. “Maybe taking that class in linguistics isn’t as silly as you think it is,” she suggests. “You might learn computer science language more than you think. A liberal arts education is much more of a boon to computer science and research in general than someone might think on the surface.”

Breaking down stereotypes and disciplinary boundaries

Keeping an open mind was part of Gillespie’s own initiation into computer science, a field that is traditionally dominated by men and that she originally perceived as being filled with “all nerds.” But after taking a few courses in the department, the young scientist soon realized that she wouldn’t be the only female student contributing to the field and that “you don’t have to be a nerd or have programmed since you were two years old”: at least at Southwestern, the computer science faculty welcome students who have no background in algorithms, systems, and databases.

She also learned that the discipline was more open-ended than expected. For example, one of her favorite classes was Computer Science I, an introductory course on programming in which students are introduced to various applications and enhance their conceptualization through a laboratory component. “The projects were really engaging. We got to build our own video game,” Gillespie remembers. “It was a lot of exploring.”

And although she now touts the importance of cross-disciplinary learning to STEM fields, Gillespie admits that she, too, had to dispel the myth of divisions between the sciences, social sciences, arts, and humanities during her early studies. “Interdisciplinary knowledge is a lot more of a help than I expected,” she says. Contrary to its representations in pop culture, “computer science is not just one person talking in a backroom to themselves. It’s very collaborative with application to other fields. That is something I found very enlightening.”

One of those applications was to her other major, chemistry. In computational chemistry, for example, researchers use digital programs and technological simulations to help characterize new compounds and materials, extract molecular data, and describe the fundamental properties of chemical reactions. “There’s a lot of chemistry involved with hardware and batteries for computers,” Gillespie explains. “I don’t focus on either of those too much, but there’s definitely an intersection between the two fields.”

Presenting and publishing as an undergraduate

Throughout the past few years, Gillespie has been working with Tweraser and Schrum on an interdisciplinary project that combines biological concepts with art and artificial intelligence in the form of computer-generated images and animations. The three researchers designed interactive evolving art systems called AnimationBreeder and 3DAnimationBreeder, in which users are given a set of images and then choose images they like. Those selections are then “used to create the next generation [of images], mimicking biological evolution,” explains Gillespie. “For example, like the survival of fittest, a human user is choosing the most-fit pictures. So the idea is that you click on the pictures you like, and the next generation will look more and more similar to what you desire to see on the screen.” Over time, as generations of new images and animations are “bred” and “evolve,” they become more complex and diverse.

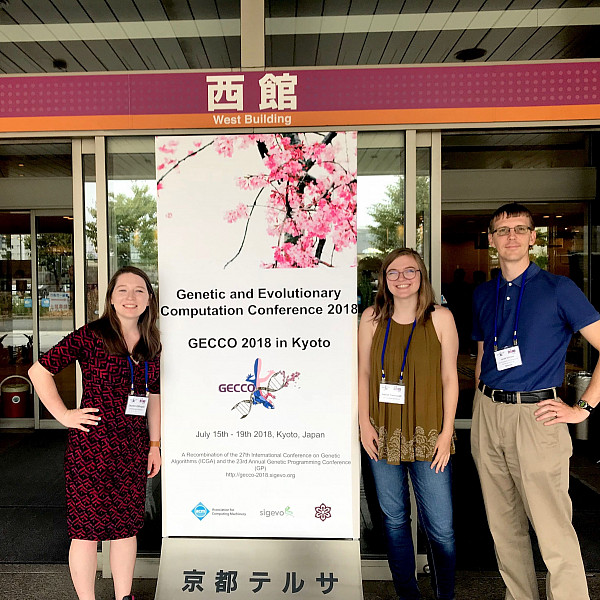

To develop AnimationBreeder and its 3D counterpart, Gillespie, Tweraser, and Schrum expanded and improved on extant programs such as PicBreeder by progressing from pixel-based images to two-dimensional .gifs and videos and 3D forms. Gillespie and her colleagues presented their work at the Genetic and Evolutionary Computation Conference (GECCO) in Kyoto, Japan, last summer and coauthored a peer-reviewed paper, “Querying Across Time to Interactively Evolve Animations,” about their collaborations—significant research accomplishments for an undergraduate.

Gillespie’s ability to speak comfortably about these complicated concepts from mathematics, computer science, and biology comes from having presented at various conferences over the years, including the 2017 GECCO conference in Berlin, Germany. However, the undergraduate admits, “It’s definitely a little overwhelming and intimidating to go to these conferences. Rubbing elbows with people who helped found the field you’re working in is a little daunting.” But Gillespie also appreciates her conference presentations as “good experiences to network” and “to see what life as an academic is like. This is the culmination of what a lot of research is, and getting to see real researchers doing real work is impressive.”

Of course, an additional perk of attending international conferences is traveling to new places. After GECCO and ALIFE, Gillespie stayed in Japan for several days. She found herself awed and inspired by the country’s temples and stone monuments, some of which are acknowledged to be the oldest known architectural structures in the world. “I fell in love with the history of Japan,” Gillespie says excitedly. “The U.S. wasn’t even a thought when this was all created. We got to see the rich culture and history of all the different shrines. The architecture was great. And the food as well!”

The patience and fortitude of undergraduate research

As Gillespie looks forward to attending graduate school after Southwestern, she looks back fondly on the trials, tribulations, and ultimate triumphs of engaging in undergraduate research. Her excitement comes across in the kind of tumble of words characteristic of the most enthusiastic academics: “Even as frustrating as it can be and how long it will take to get something to work, the best feeling is when … finally, one day, it all comes together, and you run your experiments, and you get your data back, and your graphs are beautiful and show what you expected. Or even if they don’t, it shows something no one has ever done this before, and you’re the one who did it. It’s a very gratifying feeling—even if a good 85% of the time it doesn’t feel very gratifying.”

Because of the time required by scholarly research, Gillespie says that patience is one crucial mindset students need to have—or learn rather quickly. “It is a very long and tedious process to do research,” she advises. “And it’s not just doing the research; it’s the grant-writing process to get the money, the actual research itself, the process of getting accepted by a journal. All of that can be a couple months to a year.” Even in a field like computer science, patience is a virtue, she says, “because it’s easy to put together a hacky solution that works, but in the long run, it’ll be worth the time and effort to have it done the right way.”

Speaking with the experience and wisdom of a much more advanced scholar, Gillespie fits right at home in the world of research. But until she graduates in May, she looks forward to spending her last couple of months on campus focusing on nonresearch activities, too. “I’m going to take it a little more easy, finally going to explore Georgetown as I haven’t before and just enjoying the atmosphere here before going off to grad school.” The senior relishes her time at Southwestern because she knows no other campus will have quite the same feel: “For me, especially the experience of getting to do research at a level like I did with Dr. Schrum, … to really have that level of dedication from a professor and that level of involvement, is, I think, unparalleled. I wouldn’t have had that opportunity at a bigger school.” But at the same time, Gillespie will miss the atmosphere of Southwestern’s close-knit campus, where she’s loved taking classes in politics as well as sculpture. “It was so hard trying to pick a major because I loved every class I took. So it’s been so nice to have the opportunity to do all the things I enjoyed without having to pick just one and that would be it,” she reflects. “Taking classes outside my major and [engaging in] research have given me different perspectives I wouldn’t have otherwise.”