Distinctive Collections

Lost and Found

Open gallery

In April 2017, it was discovered during an insurance appraisal that 314 items had been stolen from the Oliver Room of the Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh. Although the investigation is still ongoing, library spokesperson Suzanne Thinnes says the items were likely stolen over an extended period of time by someone familiar with the Oliver Room and its holdings.

While this is certainly a notable recent case of library theft, it is not a new phenomenon, especially in the state of Texas. Among Texana collectors in the 1960s and 1970s, it was a well-known “secret” that many of the items for sale on the market were either stolen from the State Archives, libraries, or county courthouses. Unfortunately, when items go missing from collections, they are often incredibly difficult to track down - especially when an item is discovered missing years after its last known use, when documentation is inadequate to provide clues as to what may have happened, and when there has been high turnover in library staff.

Our reality in Special Collections is that items sometimes go missing or are presumed stolen. Some of these stories may never have a happy ending, but some of them do.

Lost

Last week, Anne wrote about Southwestern’s collection of rare editions of the works of J. Frank Dobie. Southwestern Special Collections is also home to many manuscripts for these works. A missing item that weighs particularly heavily on our hearts is the original handwritten manuscript for “J. Frank Dobie on Libraries,” a short essay originally published in the Cotulla Record for LaSalle County Library in 1950. Dobie wrote this piece for Isabel Gaddis, a Southwestern University Special Collections donor, when she served as Chairman of the LaSalle County Library Board. In this essay, Dobie extols the value of a public library and advocates for increased funding from the county. Dobie writes:

You can’t always judge the value of a public library by the number of slips showing how many books are drawn out during a month or a year. One book can unlock in one person something that may lead to thought and action that will influence many lives - even a nation’s destiny. Everybody knows that this world, which includes the United States, is in a precarious condition. “This haggard world” Churchill calls it. Its salvation will not be through more atomic bombs and new hydrogen bombs. It will be through clear thinking.

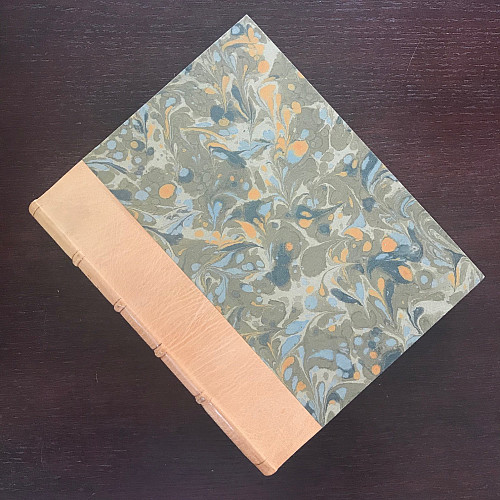

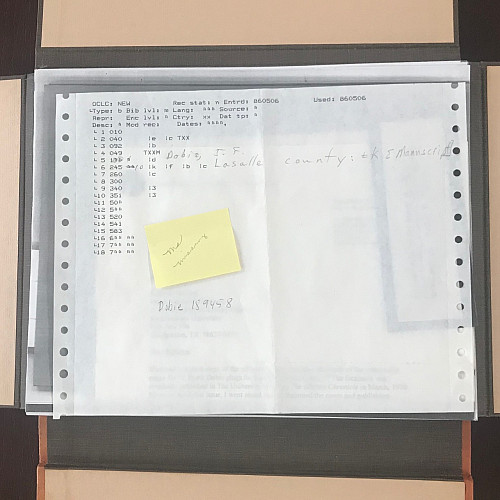

This item is shelved alongside our other original Dobie manuscripts in custom slipcases made by Ernest W. Brunner of Switzerland. Inside the beautiful slipcase for “J. Frank Dobie on Libraries,” there is a printout of the MARC record with a miniature post-it note that says “MS missing.” There is no date on this note. Other than this note, we have no leads on where the manuscript went or how long it has been missing. Also in the box is a photocopy of The Library Chronicle of the University of Texas at Austin, volume 1, March 1970, in which the editors printed a facsimile of the manuscript provided by Isabel Gaddis. All information and quotes in this blog post come from this photocopy, which may be the only record of this incredible manuscript that we can obtain.

Found

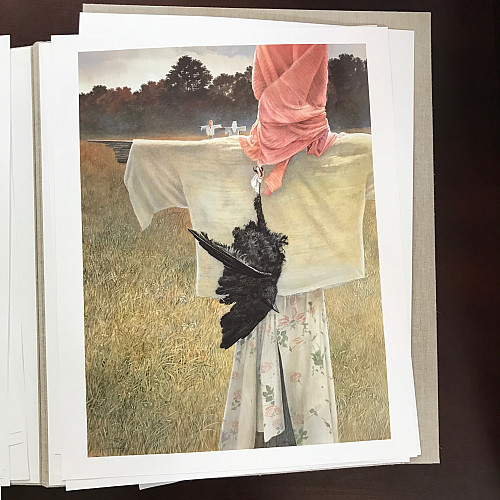

Our copy of the Gentling brothers’ limited-edition 1986 elephant folio, “Of Birds and Texas,” had also been missing its first portfolio since before any of our current staff were hired. While the record for the first portfolio was in our catalogue, it was missing from the stacks, and no former employee left any reason for us to think it was being kept in an alternate location.

While we might otherwise assume this item had been stolen, the sheer size and weight of the elephant folio caused us to doubt this as a likely scenario.

Last summer, Jason and I were walking through the stacks to find another item, and Jason happened to look up at the top of one of our bookshelves. Stacked on top of it was a large, nondescript, unlabeled block of styrofoam that I had presumed to be leftover packing materials left up there by a former employee. On an impulse, Jason decided to take the styrofoam down off the bookshelf.

Encased in the styrofoam and yet to be unpacked, as it turns out, was the first Gentling portfolio. While we still don’t know why it was left on top of a bookshelf in styrofoam all these years - perhaps it had never made it through the complete acquisition process and was forgotten - we’re happy that the two portfolios were finally reunited.

Emily Higgs, Special Collections Intern